Banquet Piece with Mince Pie

1635

Artist, Dutch, 1594 - 1680

In 1648 a contemporary writer noted that Willem Claesz Heda was a specialist in breakfast and banquet still lifes, painting "fruit, and all kinds of knick-knacks." At first sight, Heda's largest known still-life painting appears to welcome the viewer to a sumptuous feast. Yet pewter plates teeter precariously over the table's edge, while a translucent goblet and a silver tazza have toppled over, indicating that the feast has already been enjoyed. A number of objects in the painting hint at the transience of worldly existence. For example, the snuffed-out candle and the iron candle snuffer symbolize the abruptness by which life can end.

Heda was a master of uniformly cool-gray or warm-tan color schemes favored in Dutch art during the 1630s. The gold, silver, pewter, and Venetian glass on top of the white tablecloth play against the neutral backdrop of the wall and the brown drape that covers the table. Starting in the mid-1600s, brighter colors would characterize the classical period of Dutch painting.

Willem Claesz Heda taught several apprentices, including his son Gerret (or Gerrit) Willemsz Heda (active 1640s and 1650s); the "sz" at the end of Claesz and Willemsz is an abbreviation for szoon, meaning "son of". Gerret's Still Life with Ham that is part of the National Gallery’s collection reveals a strong debt to his father Willem's style and motifs.

West Building Main Floor, Gallery 50

Artwork overview

-

Medium

oil on canvas

-

Credit Line

-

Dimensions

overall: 106.7 x 111.1 cm (42 x 43 3/4 in.)

framed: 143.8 x 147 x 10.5 cm (56 5/8 x 57 7/8 x 4 1/8 in.) -

Accession

1991.87.1

More About this Artwork

Article: The Deadly Business of the Dutch Quest for Salt

The salt we see in 17th-century still lifes was central to the Dutch economy—and Dutch colonialism.

Artwork history & notes

Provenance

Private collection, the Netherlands; acquired 1948 by private collection; by inheritance to a subsequent owner;[1] (sale, Ader-Picard-Tajan, Paris, 22 June 1990, no. 39); purchased by (Galerie Sanct Lucas, Vienna; Bruno Meissner, Zurich; and Otto Naumann, New York); sold 27 February 1991 to NGA.

[1] According to the 1990 Ader-Picard-Tajan auction catalogue.

Associated Names

Exhibition History

2004

Pieter Claesz: Master of Haarlem Still Life, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; Kunsthaus Zürich; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2004-2005, not in catalogue (shown only in Washington).

Bibliography

1995

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, 1995: 99-102, color repro. 101.

1997

Brusati, Celeste. "Natural Artifice and Material Values in Dutch Still Life." In Looking at Seventeenth-century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered. Edited by Wayne E. Franits. Cambridge, 1997: 145, fig. 92.

2000

Kirsh, Andrea, and Rustin S. Levenson. Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies. Materials and Meaning in the Fine Arts 1. New Haven, 2000: 262.

2003

Gregory, Quint (Henry D. Gregory V)."Tabletop still lifes in Haarlem, c. 1610-1660: a study of the relationships between form and meaning." Ph.D. diss., Dept. of Art History and Archaeology, University of Maryland, College Park, 2003: 3-18 and passim.

2004

Hand, John Oliver. National Gallery of Art: Master Paintings from the Collection. Washington and New York, 2004: 192-193, no. 153, color repro.

Gregory, Quint (Henry D. Gregory V). "A Repast to Savor: Narrative and Meaning in Pieter Claesz's Still Life." In Pieter Claesz : master of Haarlem still life. Edited by Pieter Biesboer. Exh. cat. Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; Kunsthaus Zürich; National Gallery of Art, Washington. Zwolle, 2004: 107, fig. 1.

2015

"Art for the Nation: The Story of the Patrons' Permanent Fund." National Gallery of Art Bulletin, no. 53 (Fall 2015):11, repro.

2020

Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. Clouds, ice, and Bounty: The Lee and Juliet Folger Collection of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2020: 150, 152, fig. 1.

2021

Barkan, Leonard. The Hungry Eye: Eating, Drinking, and European Culture from Rome to the Renaissance. Princeton, 2021: 220, fig. 5.22.

2024

Dickerson III, C.D. "Gifts and Acquisitions."Art for the Nation no. 68 (Spring 2024): 17, repro.

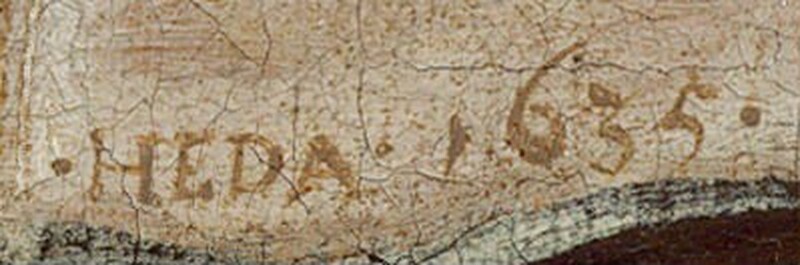

Inscriptions

lower right on edge of tablecloth: .HEDA.1635.; lower left on edge of tablecloth: (unidentified monogram) [1]

[1] This unidentified monogram is an unusual feature of this painting, as it does not appear to be an artist’s monogram. Dr. Pieter Biesboer, former curator at the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, has suggested (verbally) that it is the mark of the linen maker.

Wikidata ID

Q20177138