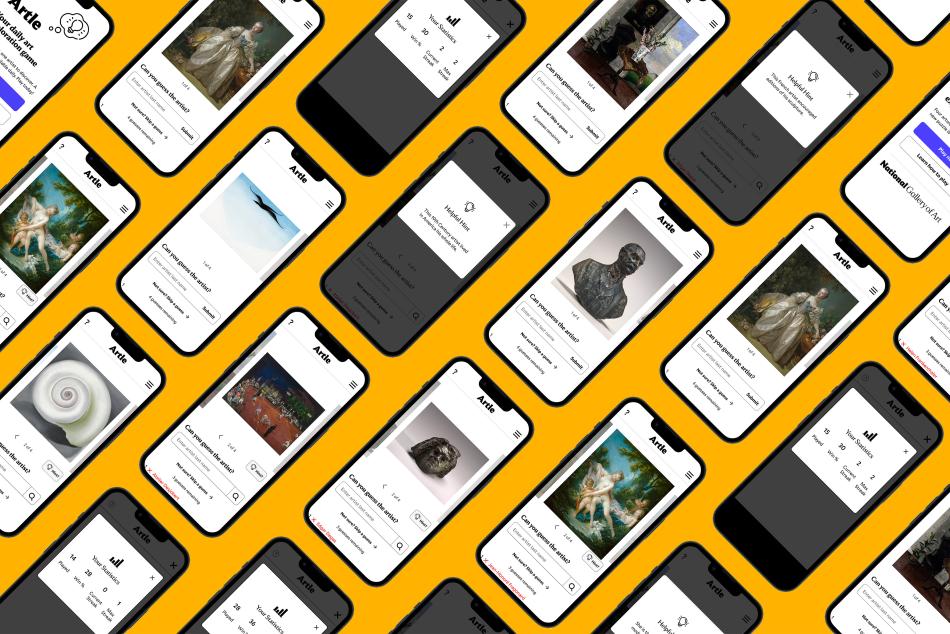

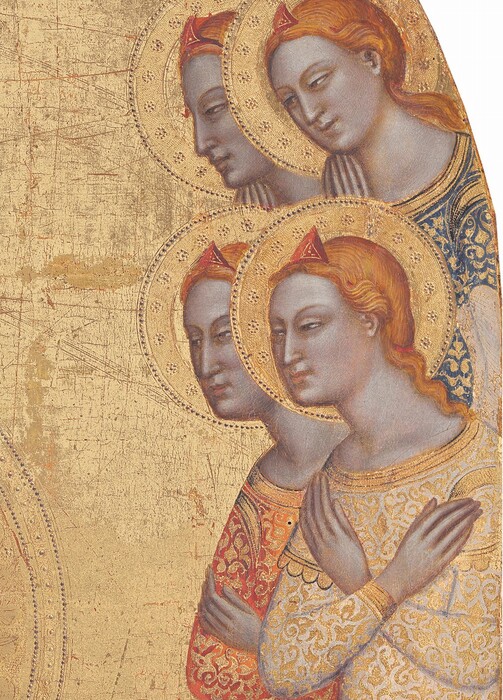

Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Madonna and Child with God the Father Blessing and Angels, c. 1370/1375

Publication History

Published online

Entry

The image of Mary seated on the ground (humus) accentuates the humility of the mother of Jesus, obedient ancilla Domini (Lk 1:38). The child’s gesture, both arms raised to his mother’s breast, alludes, in turn, to another theme: the suckling of her child, a very ancient aspect of Marian iconography. In the medieval interpretation, at a time when the Virgin was often considered the symbol of the Church, the motif also alluded to the spiritual nourishment offered by the Church to the faithful. As is common in paintings of the period, the stars painted on Mary’s shoulders allude to the popular etymology of her name. The composition—as it is developed here—presumably was based on a famous model that perhaps had originated in the shop of Bernardo Daddi. It enjoyed considerable success in Florentine painting of the second half of the fourteenth century and even later: numerous versions of the composition are known, many of which apparently derive directly from this image in the Gallery. This painting, therefore, must have been prominently displayed in a church of the city, and familiar to devotees.

Osvald Sirén (1917) published the panel as an autograph work of Andrea Orcagna, with a dating around 1350. The proposal was widely accepted in the art historical literature, though Richard Offner initially stated (see Lehman 1928), that it was the work of an assistant to the artist. Bernard Berenson also at first proposed an attribution to Orcagna (Lehman 1928), but later (1931, 1932, 1936) suggested that the master executed the painting in collaboration with the youthful Jacopo di Cione, Orcagna’s brother. The attribution to Jacopo himself was suggested by Hans Dietrich Gronau (1932, 1933); Frederick Antal (1948); Offner (in Shorr 1954 and Offner 1962), though the same scholar in 1965 and 1967 detected the collaboration of assistants in the work; Mirella Levi d’Ancona (1957); Klara Steinweg (1957–1959 and Offner and Steinweg 1969); Miklós Boskovits (1962, 1967, 1975); Alessandro Parronchi (1964); Luisa Marcucci (1965); Barbara Klesse (1967 with admission of workshop assistance); Carl Huter (1970); Marvin Eisenberg (1989); Barbara Deimling (1991, 2000, 2001, 2009); Paul Joannides (1993); Erling Skaug (1994); Mojmir S. Frinta (1998); Daniela Parenti (2001); Costanza Baldini (2003); Angelo Tartuferi (2003, 2004); Carl B. Strehlke (2004); and in Galleria dell’Accademia 2010. However, the painting entered the Kress Collection (NGA 1945) as a joint work by Orcagna and Jacopo, probably at Berenson’s suggestion, and this proposal met with wide support: it was accepted by Millard Meiss (1951); Berenson (1963); NGA (1965, 1968, 1985); Fern Rusk Shapley (1966, but in 1979 she attributed the painting to Jacopo alone, or to Jacopo and his workshop); Deborah Strom (1980); Perri Lee Roberts (1993); Marilena Tamassia (1995); and Gaudenz Freuler (1994, 1997). More recently, the proposal by Pietro Toesca (1951) and Michel Laclotte (1956), who both considered the painting a product of the shop of Andrea Orcagna, has met with some favor, though modified by some to suggest it is substantially an autograph work by Orcagna (Laclotte and Mognetti 1976; Padoa Rizzo 1981; Kreytenberg 1990, 1991, 1995, 1996, 1998, 2000; Franci 2002; Laclotte and Moench 2005; Freuler 2006).

As for the dating of our panel, its attribution, even partial, to Orcagna implies that it was completed by or not much later than 1368, the year of the artist’s death. Sirén (1917) dated the painting to c. 1350, and Raimond van Marle (1924) substantially accepted the proposal. Gronau (1932), though he too supported an attribution to Jacopo, dated the painting c. 1360–1370. Presumably Berenson (1936) had a similar dating in mind when classifying the panel as a youthful work by Jacopo. So did Meiss (1951), who defined the painting as “probably designed by Orcagna and partly executed by Jacopo di Cione.” Levi d’Ancona (1957) suggested a date of 1360–1365 for the painting; the National Gallery of Art (1965) catalog, c. 1360. Steinweg (1957–1959), in turn, dated the panel to after the death of Orcagna in 1368, and Shapley (1966) to 1370. Some scholars who have argued in favor of Jacopo’s authorship have suggested a dating as late as 1370–1380. Offner and Steinweg (1965) dated the panel c. 1380, followed by Klesse (1967) and Carl Huter (1970). Huter detected in the painting, unconvincingly, a reflection of the vision of the Nativity of Our Lord attributed to Saint Birgitta (Bridget) of Sweden during her journey to the Holy Land. Reconsidering her earlier opinion, Steinweg (Offner and Steinweg 1965) called the panel “Jacopo di Cione’s latest work.” She was followed by Shapley (1979), according to whom it was painted “perhaps as late as the 1380s,” while Boskovits (1975) proposed a date of c. 1370–1375. The question is complicated by the problems relating to the reconstruction of the youthful activity of Jacopo di Cione, and also by the poor condition of the former Stoclet Madonna, which, with its date of 1362, represents the only secure chronological point of reference for the artist’s initial phase.

The hypothesis that the panel is an autograph work by Orcagna clearly would need to be verified by comparing it with authenticated works of this artist, or works generally recognized as by his hand, in particular the polyptych in the Strozzi Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, signed and dated 1357; the fresco of the Crucifixion in Santa Marta a Montughi (Florence); the triptych in the Rijksmuseum at Amsterdam, dated 1350; and the polyptych in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, probably dating to 1353. These paintings illustrate the main stages in Orcagna’s career in the years preceding the altarpiece of 1357. His last stylistic phase, in turn, is attested by the frescoes in the former refectory of Santo Spirito in Florence, now Fondazione Salvatore Romano, and the Pentecost triptych in the Galleria dell’Accademia. The presence of the master in the Fondazione Romano frescoes and the Accademia triptych is often judged partial, but even if the involvement of assistants can freely be admitted, especially in the fresco of large dimensions, Andrea’s direct intervention is undoubtedly revealed in various parts of the cycle.

The stylistic features that distinguish the art of Orcagna in the last two decades of his life emerge from a comparative assessment of the above-cited paintings. They document his gradual transition from ample, softly modeled and majestic forms, defined by sharp contours, chiaroscuro effects of great delicacy, and a predilection for the abstract purity of large sweeping expanses of color, to a quite different manner. His late works are characterized indeed by a more marked, even at times brutal, accentuation of the three-dimensionality of bodies. Apparently, after the experience of realizing the sculptures for the tabernacle of Orsanmichele (1352–1360), Orcagna was intent on reproducing in his paintings a two-dimensional simulation of the effect of reliefs that stand out clearly, with smooth and lustrous surfaces, from a monochromatic, enamel-like ground. His narrative scenes are characterized by an extreme reduction to essentials in composition and by the predominant role of the human figure, whose plasticity is accentuated by being delineated, as if contre-jour, against the gold ground.

The artist of the Madonna in the Gallery, however, does not seem to have aimed at results of this kind. The delicate passages of chiaroscuro confer softness on the flesh parts, while the gradual darkening of the varicolored marble floor on which Mary is sitting subtly accentuates its extension into depth. In particular the foreshortened prayer book in the foreground and the undulating lower hem of the Virgin’s mantle are painted with a deliberate illusionistic effect: the latter in particular projects beyond the front edge of the marble floor that defines the frame of the image, and thus seems to extend into the real space of the spectator. Such illusionistic effects are, as far as his generally recognized works show, alien to Orcagna’s repertoire. In the Gallery panel, moreover, there is no trace of the metallic hardness and sheen of forms. Nor does the drapery show any of the angular folds with deep, sharp-edged undercutting that are usually found in Andrea’s paintings, especially in those dating to the seventh decade, such as the abovementioned triptych of the Pentecost or the triptych of Saint Matthew in the Uffizi, Florence, a work begun by the artist but completed by a workshop assistant after Orcagna’s death in 1368. Only some secondary passages, such as the fluttering angels in the central panel of the Pentecost altarpiece (of which Jacopo’s partial execution has been proposed), recall the more fluid drawing and more relaxed emotional climate of the Gallery panel.

It is in fact in the oeuvre of Jacopo di Cione that our panel finds its closest affinities, in particular with the polyptych painted between 1370 and 1371 for the Florentine church of San Pier Maggiore and with the Florentine Pala della Zecca (now in the Galleria dell’Accademia) for which Jacopo received final payment in 1373. Close relatives of the face of Mary in the Gallery panel seem to me that of the crowned Virgin in the Pala della Zecca and that of the Madonna of Humility, also now in the Galleria dell’Accademia. The Christ child, in turn, is closely akin to counterparts both in the latter panel and in the versions of the Madonna and Child in the church of Santi Apostoli in Florence and in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. The tiered angels in the upper part of our painting are almost identical to those in the two gabled panels from the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece , now in the National Gallery in London. The analogies can also be extended to the blessing God the Father , who recalls the Christ in the Pala della Zecca and some of the saints, too, in the polyptych of San Pier Maggiore . In most of these images the modeling is now impoverished as a result of repeated, over-energetic cleaning, but the fluency of design, spaciousness of composition, and the artist’s ever greater attention to three-dimensional effects confirm the attribution of the painting to Jacopo. Typical of Jacopo di Cione, in addition, are such details as Mary’s tapering fingers and the mood of subtle languor that characterizes her face. The pursuit of gracefulness of pose and the delicate chiaroscuro in the modeling strongly suggest that the Gallery panel belongs to a phase preceding the artist’s output in the 1380s and was probably produced in the years c. 1370/1375, probably closer to the second of these dates.

Technical Summary

The support is constructed with several (probably five) planks of wood with vertical grain. The painted surface is surrounded by unpainted edges, originally covered by the now lost engaged frame. The panel has been thinned down to its present thickness of 0.6 cm, backed by an additional panel, and cradled by Stephen Pichetto in 1944. It has suffered from worm damage in the past. The painting was executed on a white

Pichetto removed a discolored varnish during his treatment in 1944. Mario Modestini removed the varnish again and