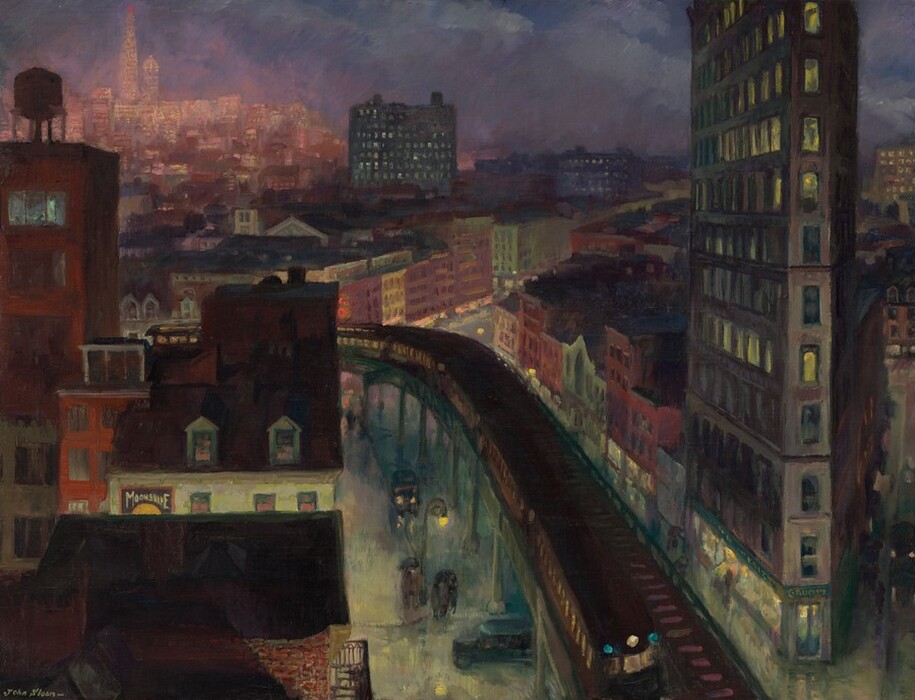

American Paintings, 1900–1945: The City from Greenwich Village, 1922

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Painted in 1922, The City from Greenwich Village is closely related to a number of John Sloan’s earlier paintings, and is the culmination of his many views of New York City. The painting’s special significance to the artist is evidenced by the fact that there are more preparatory drawings associated with this work than any of his other pictures. Sloan’s book, Gist of Art, provides a lengthy description of The City from Greenwich Village:

Looking south over lower Sixth Avenue from the roof of my Washington Place studio, on a winter evening. The distant lights of the great office buildings downtown are seen in the gathering darkness. The triangular loft building on the right had contained my studio for three years before. Although painted from memory it seems thoroughly convincing in its handling of light and space. The spot on which the spectator stands is now an imaginary point since all the buildings as far as the turn of the elevated have been removed, and Sixth Avenue has been extended straight down to the business district. The picture makes a record of the beauty of the older city which is giving way to the chopped-out towers of the modern New York.

Unlike the majority of Sloan’s earlier and more spontaneously executed realist paintings that represent episodes in the daily lives of New Yorkers, the subject of The City from Greenwich Village is the city itself. This panoramic aerial view from the roof of Sloan’s studio apartment at 88 Washington Place, where he lived from 1915 to 1927, shows lower Sixth Avenue on a rainy evening as an elevated train turns the corner at Third Street and heads north. The viewer’s eye is led over the picturesque rooftops to the distant upper left, where brilliantly illuminated skyscrapers are silhouetted on the horizon. The taller one, on the left, is the 60-story gothic revival Woolworth Building (completed in 1913, designed by Cass Gilbert, and the world’s tallest building at that time), and at its right is the Singer Tower (1908). The train boldly bisects the composition, separating the low, dormered structures on the left from the triangular loft building that rises up on the right, beyond the upper limit of the composition.

Sloan included the elevated train in a number of important early paintings, in which it serves as a backdrop for some aspect of human activity. But here, only a few pedestrians have ventured forth into the inclement night, and two automobiles appear in the center foreground. The City from Greenwich Village is closely related to Jefferson Market , a view of the Sixth Avenue train seen from the north window of Sloan’s fifth-story, Washington Place apartment. Additionally, the Varitype Building (a triangular structure in which Sloan had leased his first Greenwich Village studio in 1912) featured in the Gallery’s painting is considerably smaller than the more famous but similarly shaped Flatiron Building, which Sloan included in his Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue (1906, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), and occupies a similar place in the composition. Sloan also depicted the Varitype Building in Cornelia Street (1920, private collection).

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of The City from Greenwich Village is Sloan’s skillful combination of natural and artificial light. The dim haze of the city is punctuated by numerous sources of electric light from the shop windows, a streetlight, and the headlights of the train and a car that are in turn reflected off the rainy surfaces of the street and buildings. The eminent historian of American art Lloyd Goodrich has noted that Sloan painted cityscapes “from a poetic viewpoint like that of the landscapist,” and observed how, in this particular work, the artist has achieved “a subtler and deeper realization of night color than any of his early works, which seem almost monochromatic by comparison.” In addition to his nuanced portrayal of urban lighting, Sloan has also commented wittily on the artifice of the modern city by including the Moonshine advertisement on the façade of the building at the lower left. “Moonshine,” a term meaning nonsense or foolish talk, was also used to describe the illicitly distilled and distributed liquor that became popular during Prohibition. Just below the fictional brand name, a truncated image of the moon evokes what the city’s artificial electric lighting so effectively obscures: natural moonlight.

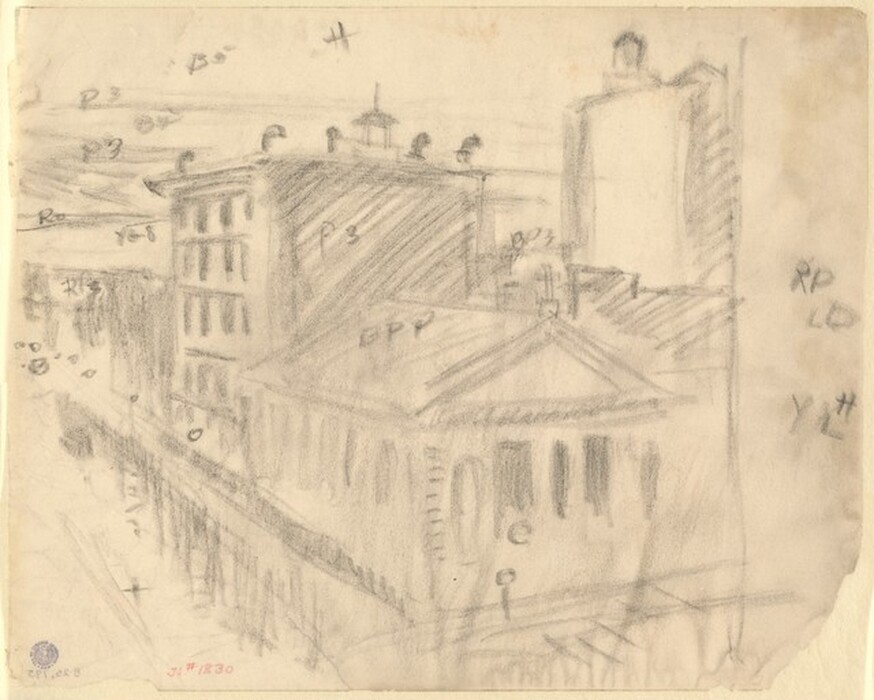

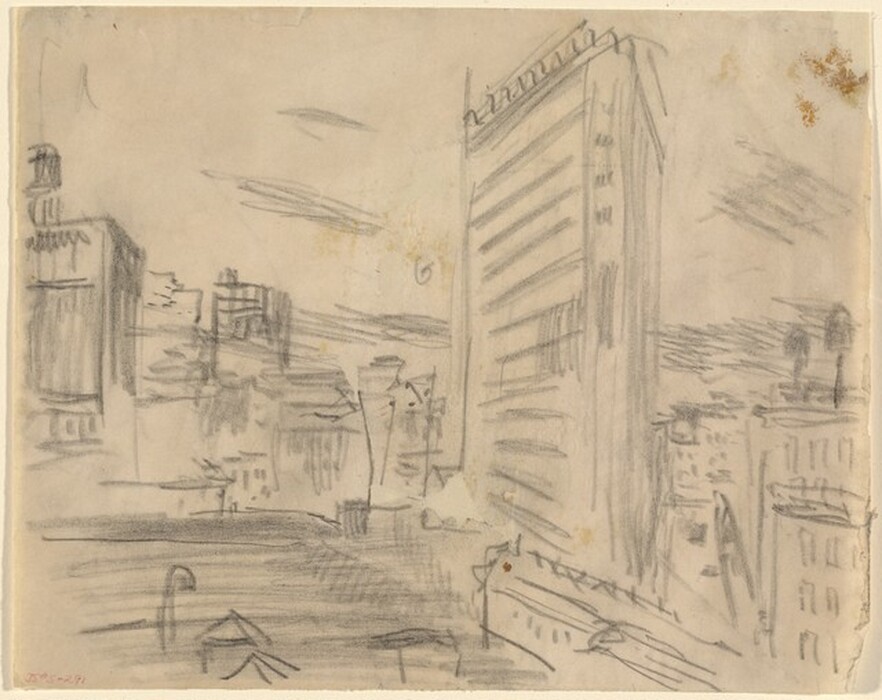

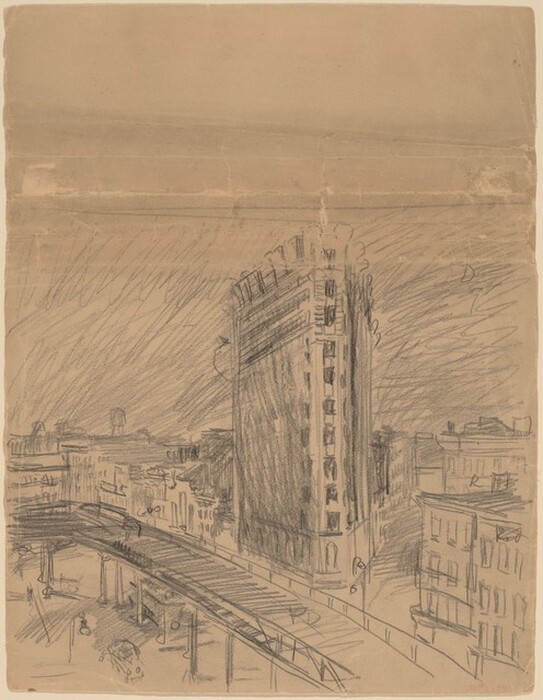

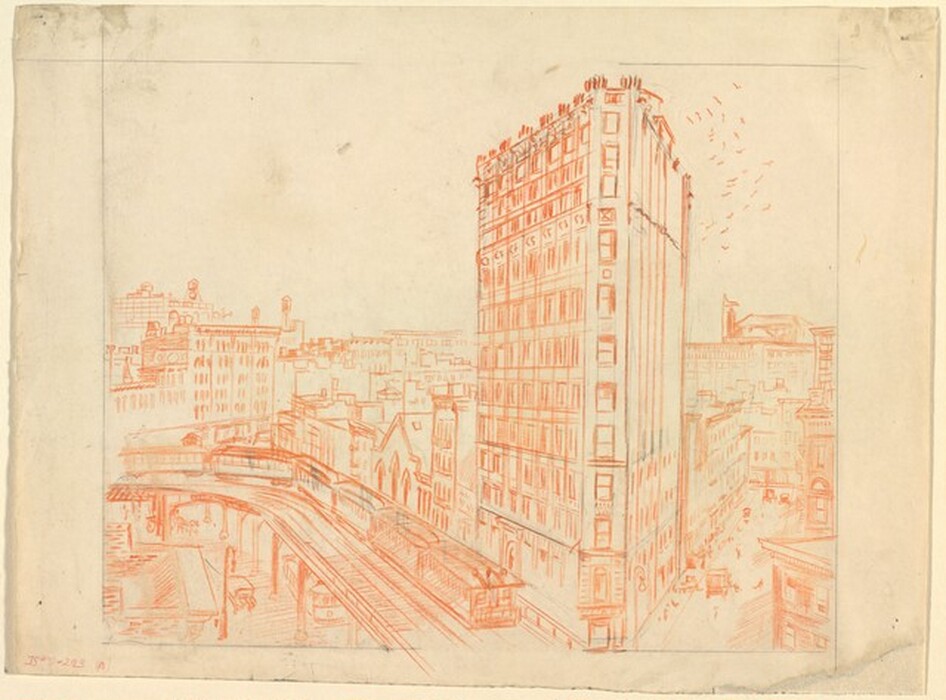

In his article on The City from Greenwich Village, David W. Scott analyzes the five preparatory studies in the Gallery’s collection and concludes that it is impossible to place them in chronological order and definitively trace the evolution of the composition , , , , . None of the drawings completely accounts for the final image. For instance, in some of the sketches, Sloan has concentrated on the triangular Varitype Building and the train but omitted the distant view of lower Manhattan and its skyscrapers. Scott also discerned in Sloan’s drawings the use of the Golden Section, a system of proportions that Sloan had advocated, in the dominant vertical plane in the composition’s center.

The detailed account of the painting that Sloan gives in Gist of Art implied that he wanted to illustrate how modernization, in the form of skyscrapers and public mass transportation systems such as elevated trains, had destroyed Greenwich Village’s formerly intimate, 19th-century ambience. The artist had lived in the Village—New York’s bohemian neighborhood—from 1912 to 1935, and during those years he had the opportunity to observe the changes wrought by urban renovation; many of the houses that he found “small and old fashioned” in 1908 were demolished to make way for modern buildings. Sloan scholar Rowland Elzea cites a quote in which the artist recalled: “Automobiles fill the streets and Prohibition turned the night life of the city into a nightmare of clubs and commercial entertainment. The city was spoiled for me.” Over the last two decades of his career Sloan rarely depicted New York.

Although Sloan may not have extolled New York's transformation into a modern metropolis in The City from Greenwich Village, neither did he completely condemn it. Despite Sloan's negative description of new buildings as “chopped out towers,” there is nothing particularly sinister in his depiction of lower Manhattan’s skyscrapers. On the contrary, The City from Greenwich Village possesses a magical quality that has led John Loughery to equate it with the Emerald City of Oz. Far from being a wholesale condemnation of modernization and progress, Sloan’s painting, like Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph Old and New New York, evokes the romanticism of the past while acknowledging contemporary realities in order to deftly capture a city in transition.

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a medium-weight, plain-weave canvas that was primed with a white ground that is not thick enough to disguise the weave of the canvas. In 1970, National Gallery of Art conservator Frank Sullivan cut the painting from its stretcher, removing the original tacking margins in the process. It was then relined with an aqueous adhesive and stretched onto a new support. The work was also cleaned and revarnished with a synthetic resin during this treatment. The paint layer is thickly applied with one layer painted over another, often with some moderate blending with the brush. For the most part, although the paint is thick the impasto and brush markings are not very pronounced. The paint layer is in good condition, with only a few small inpainted but not filled losses located in the upper portion of the work.