American Paintings, 1900–1945: Cows in Pasture, 1923

Publication History

Published online

Entry

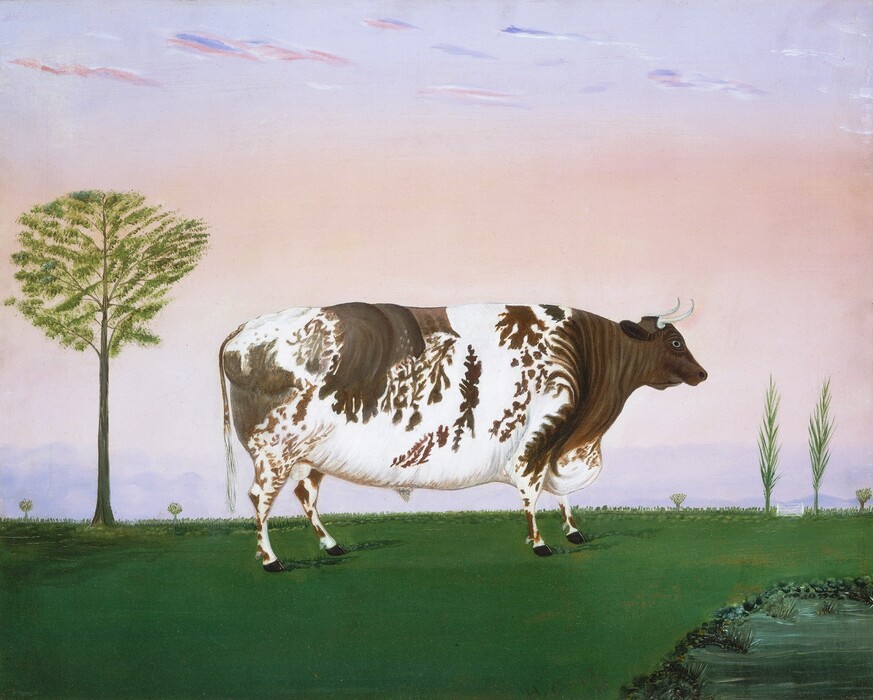

Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s early paintings, prints, and drawings feature odd, humorous, and even disconcerting subjects: frightened-looking babies with animals and anthropomorphic vegetation, for example. When he tackled more conventional motifs, such as still lifes, landscapes, or nudes, he depicted them in a quasi-surrealistic style, from dizzying perspectives, or in odd arrangements with curious props. Cows in Pasture, ostensibly a straightforward view of a coastal New England dairy farm, is a prime example of Kuniyoshi’s subtle “strangeness,” as a critic characterized the artist’s early work.

Kuniyoshi’s favorite early subject was the cow; the artist estimated he painted some 60 cow pictures during the mid-1920s. His preoccupation with the animal and the gravity with which he treated it earned him the label of satirist, a charge he would later counter:

I wasn’t trying to be funny but everyone thought I was. I was painting cows and cows at that time because somehow I felt very near to the cow. . . . You see, I was born, judging by the Japanese calendar, in a “cow year.” According to legend I believed my fate to be guided, more or less, by the bovine kingdom.

Kuniyoshi’s association with a bovine guardian spirit prompts an autobiographical interpretation of Cows in Pasture. The young artist was enjoying a spell of good fortune at this time. He had been given his first solo exhibition in 1922 at the Daniel Gallery in New York, having recently found a patron in the respected painter, critic, and teacher Hamilton Easter Field. In 1919, Field invited Kuniyoshi to attend classes at his art colony in Ogunquit, Maine, a coastal village about 70 miles north of Boston, where Kuniyoshi married Katherine Schmidt, a classmate at the Art Students League.

Kuniyoshi cultivated his infatuation with the cow in Ogunquit. As he wrote to his friend the artist Reginald Marsh in 1922: “Things round here very quiet at present and . . . just [suits] . . . us[.] [W]e started working . . . last week and as usually [here] I begin with a cow[.]” Maine’s “severe landscape,” which Kuniyoshi later reverently called his “God,” provided the setting for Cows in Pasture. Maine was also where Kuniyoshi and his Ogunquit compatriots mined American folk art for the stylistic inspiration evident in Cows in Pasture. “Most of the summer colony in Maine last year,” wrote one observer in 1924, “went mad on the subject of American primitives, and . . . the Kuniyoshis stripped all the cupboards bare of primitives in the Maine antique shops.”

The large scale and flat profiles of Kuniyoshi’s cattle in Cows in Pasture recall the kinds of folk art the Ogunquit artists admired, especially 18th- and 19th-century livestock portraits commissioned by proud farmers . But the expressive eyes of Kuniyoshi’s cows endow these animals with a sentience that is more reminiscent of the benign beasts in Edward Hicks’s allegorical Peaceable Kingdom pictures (see, for example, ). Hicks’s canvases depict the fulfillment of Isaiah’s Old Testament prophecy, in which the calf and the lion live happily together.

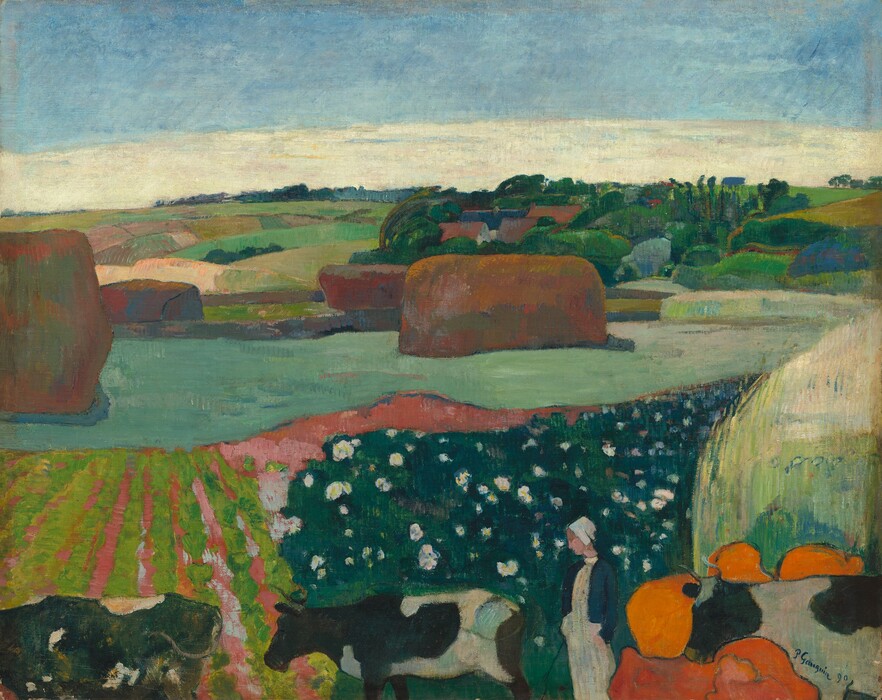

Cows in Pasture, though, does not merely mimic a naïve style. Rather, the painting testifies to Kuniyoshi’s attempt to reconcile a complex set of artistic traditions, cultural influences, and personal symbols. The disjunctive scale, peculiar geometries, unstable perspective, and oversize animal characters are reminiscent of recent developments in avant-garde European art. Following the 1913 Armory Show, Kuniyoshi admitted that he “tried . . . radical kind[s] of painting without understanding [and] imitated [the] worst side of Van Gogh, Cézanne, Gauguin.” Paul Cézanne’s influence is apparent in the geometric emphasis in Cows in Pasture, particularly in the accordioned cliff faces, boxy farm buildings, and triangular cows. The work of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin appears to have been even more compelling to Kuniyoshi; both artists borrowed their expressive line, flat areas of intense color, and dramatic asymmetry from the Japanese art that had surrounded Kuniyoshi when he was younger . “My tendency,” he said, “was two-dimensional. My inheritance was shape-painting, like kakemonos [scroll-painting].”

Kuniyoshi’s artistic circle saw evidence of modernism’s native roots in the formal similarities between European modernism and American folk art and colonial art. Americana was championed as a valid, indigenous source for modern art. This subtext might have resonated more significantly for the Japanese-born Kuniyoshi. Painting reassuring subjects with precedents in early American art enabled him to express his interest in recent European painterly innovations and traditional Japanese graphic techniques without fear of censure or judgment of foreignness. That Kuniyoshi was not completely successful was hinted at by the critic Henry McBride, who contended: “Those unacquainted with the art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi . . . will probably rub their eyes and wonder whether they are in Japan, Maine or Mars.”

Kuniyoshi eventually abandoned the barnyard subjects and what critics saw as the “mischievous humor” of his earlier paintings. By the 1940s his “queer rectangular cows” were replaced with desolate landscapes and still lifes composed of wrecked objects, masks, and semilegible antiwar rhetoric . It is quite possible that this shift occurred in response to the political and social developments of the intervening decades. As a Japanese immigrant, Kuniyoshi was the subject of intense suspicion following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. He was questioned by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and was briefly placed under house arrest, despite being outspokenly prodemocracy, anti-imperialist, and antifascist. He articulated the dire situation in a letter to his friend and the first owner of Cows in Pasture, the artist George Biddle, on December 11, 1941: “A few short days has changed my status in this country, although I have not changed at all.” It is not difficult to imagine that Kuniyoshi’s “broken, worn, used up . . . rotting” subjects of the 1940s reflect the artist’s personal difficulties, just as his talismanic cows of the 1920s were products of that earlier, happier time. Kuniyoshi, after all, described his creative process as “feeling, imagination and intuition mingled with reality [that] creates more than actuality, evokes an inner meaning indicative of one’s experience, time, circumstances and environment. This is reality.”

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a plain-weave, medium-weight, pre-primed canvas and is lined with a similar weight linen using a wax adhesive. The tacking margins are intact, indicating that the painting is very close to its original dimensions. The stretcher is a modern five-member, expansion bolt replacement. The commercially prepared ground is a grayish off-white.

In general, the paint has been applied as a thin, fluid paste that builds up the composition in a series of multiple layers. Delicate, flickering touches of a small brush are visible in many areas. Although the paint is mostly opaque, in some places, for example the red barn in the upper center, it is sufficiently thin and transparent that the glow of the light-colored ground is visible through the red paint. In some of the rocks and foliage the paint is applied more freely and thickly, with noticeable brushmarks and dabs of low impasto. There are a few places (as in the haystack at left and above and to the right of the red cow) where the artist appears to have deliberately abraded previously applied paint with a knife or other sharp tool and then continued painting.

In reflected light a large design element is visible that is now completely painted out. It appears to be a triangular shape surmounted by an oval in and above the area of the black cow. In infrared examination the painting appears to follow a dark outline probably made with a pencil. There is a drawn shape to the left of the black cow’s head that is not discernible, although it does have some foliage-like elements. This shape does not appear in the final painting. Although the shape visible in reflected light (described above) does not appear in infrared, in the x-radiograph it is clear that there was once a figure that seemed to be riding the black cow that is now painted out. In 1974 the picture was treated at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, where it was wax-lined and mounted to a new stretcher. Grime was also removed from the surface and the painting was varnished and retouched. At present, this synthetic varnish applied in 1974 has a somewhat glossy appearance with a slightly hazy surface. It appears that, prior to this varnish application, the painting had been left unvarnished by the artist.