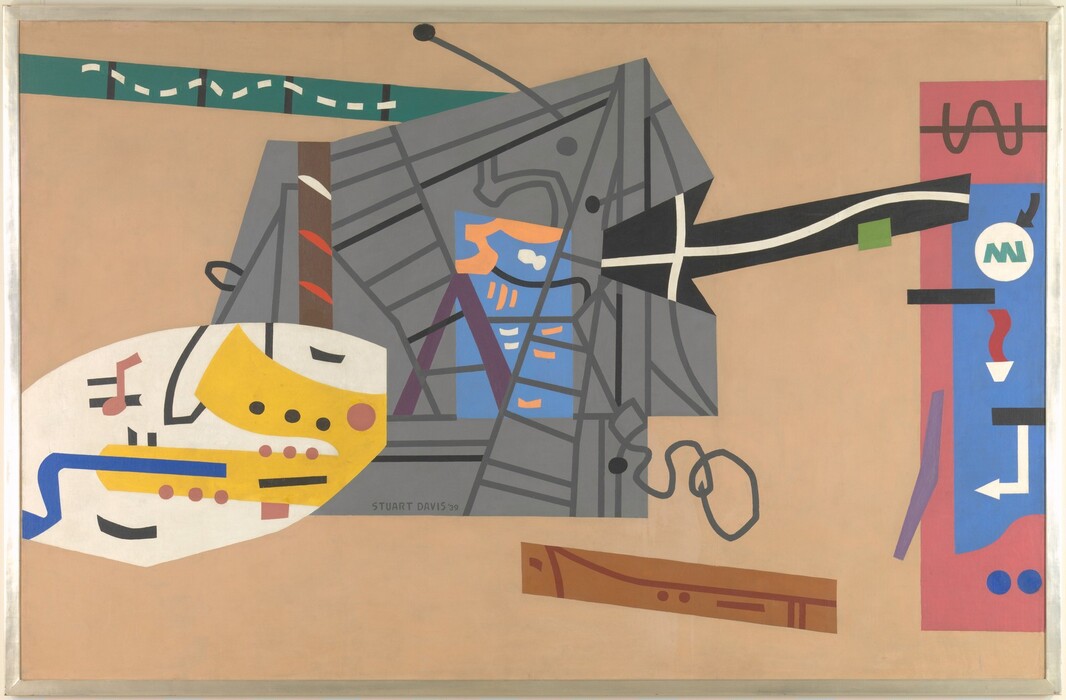

American Paintings, 1900–1945: Study for "Swing Landscape", 1937-1938

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Swing Landscape was the first of two commissions that Stuart Davis received from the Mural Division of the Federal Art Project (FAP), an agency of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), to make large-scale paintings for specific sites in New York. The other was Mural for Studio B, WNYC, Municipal Broadcasting Company . The 1930s were a great era of mural painting in the United States, and Davis, along with such artists as Thomas Hart Benton, Arshile Gorky, and Philip Guston, was an important participant.

In the fall of 1936, Burgoyne Diller, the head of the Mural Division and a painter in his own right, convinced the New York Housing Authority to commission artists to decorate some basement social rooms in the Williamsburg Houses, a massive, new public housing project in Brooklyn. A dozen artists were chosen to submit work, and, while Davis’s painting was never installed, it turned out to be a watershed in his development. The word “swing” in the title is surely a double reference to the ceaseless shifting of forms in the composition (there are almost no true verticals to be found) and to the often loud, always pulsating jazz music that Davis loved. When the painting was shown in May 1938 at an exhibition of murals at the Federal Art Gallery in New York, the painter John Graham declared it (as Davis noted in his desk calendar) “the greatest American painting.”

According to the authors of Davis’s catalogue raisonné, the present work must be the one-quarter-scale oil study that Davis finished in the spring of 1937 to serve as his proposal to the WPA in Washington. It was approved in June, and for the next 11 months Davis, with two assistants, transferred the design to a large canvas in the FAP studio on 42nd Street in New York. A black-and-white photograph of the oil sketch has been found in the FAP records. Comparison with the study reveals that Davis made changes to the study (most notably adding the yellow and white rigging to the mast at upper left) after it was returned to him, suggesting that he continued to use it as a working model. The finished mural closely follows the outlines of the study but is brighter and more complex; for Davis, a preliminary study was never more than an armature for the improvisational act of painting.

Davis at this time was in his mid-forties, an established figure in the New York art world with a long career behind him, and yet like so many artists during the Depression he lived in dire poverty. The small degree of commerical and critical success he had started to enjoy in the 1920s had evaporated, and, rather than continue to paint much after the stock market crash, he threw himself into political organizing on behalf of rights for his fellow artists, holding a series of increasingly responsible positions from 1933 to 1940 in the John Reed Club, the Artists Union, the Artists’ Committee of Action, their magazine Art Front, and finally the American Artists’ Congress. He was elected president of that body in December 1937 but resigned in protest in April 1940 along with several others when it endorsed the Soviet invasion of Finland that had taken place the previous winter.

This record of activity might suggest that Davis was a political artist. In fact, he kept his art and politics separate, consistently refusing to make propaganda on behalf of the pro-labor, antifascist causes that he embraced. It is true that his two murals preceding Swing Landscape—New York Mural and Mural (Radio City Men’s Lounge: Men without Women), both from 1932—were full of legible references to urban life and issues. In Swing Landscape, Davis stepped back from the immediate spectacle of the contemporary world, and toward abstraction. Using one of his favorite subjects, the harbor of Gloucester, Massachusetts (where he had summered since 1915) with its largely bygone wind-powered fishing schooners, Davis jammed together fragments of many existing sketches and paintings to create a work that is filled from end to end with jagged, jangling forms. Bricks, buoys, rigging, piers, ropes, smoke, water, and perhaps even a sunrise can be detected, and the whole is bracketed by two pale gray strips, one for the sky at the top and one representing the dock along the bottom. But between and across these bands Davis unleashes a great improvisation of color and rhythm—the large, bold, abstract, muscular forms that would increasingly characterize his work until his death in 1964.

For all his interest in jazz and the practice of improvisation, Davis was traditional in his reliance on sketches, studies, and previous work, both in general and especially as he approached this major commission. The catalogue raisonné lists almost 20 related works from 1931 to 1937, including five paintings, six gouaches, and seven sketchbook drawings. The painting Landscape with Drying Sails (1931–1932, Columbus Museum of Art) provided the basic composition and motifs for the left half of the mural, and another painting, American Waterfront, Analogical Emblem (1934, private collection, San Francisco), served the same function for the right half. The works on paper include one line drawing and three gouaches of the entire composition; the rest are sketchbook pages from the early 1930s that he plundered for specific elements of the final work.

Comparison of our study to the finished mural reveals a great number of changes, not in the basic composition but in color choices and level of detail. For example, the buoy at lower left, which is simply a brown silhouette in the study, gains considerable detail and color (orange, brick red, yellow, blue, and black); the yellow house above it, a simple shape in the study, gains a black window with a purple lintel below it; and the chunky red puff of smoke emerging from the roof of the house gets defined in two different colors, suggesting depth and movement. Other added elements not present in the study include bricks, ripples, additional rigging, and pieces of rope (although to describe these representationally misses the fact that they are equally important as lively abstract elements). Interestingly, not all the additions to the study are bright and jazzy: the yellow and white rigging on the mast at left has become turquoise and ochre in the finished mural.

Why the finished work was never installed at its intended home remains a mystery. No relevant documentation has been found, but it is tempting to speculate. The works that were chosen for installation are quite different in character from Swing Landscape, whose packed forms, bright colors, and all-over composition bear little relation to their more delicate shapes, rendered in muted colors and floating in shallow space. The four artists whose works were chosen—Ilya Bolotowsky, Paul Kelpe, Balcomb Greene, and Albert Swinden—were all founding members of American Abstract Artists, a group that was devoted to the propagation and development of European styles coming variously out of the De Stijl, constructivism, and Bauhaus schools. Davis himself had worked through plenty of European modern art by that point, and he was intent on developing an original, American style. This in itself does not fully explain the mystery since the works were to be installed in different buildings, so direct clashing would not have been an issue; but it does suggest that style and taste might have been factors in the decision not to install Swing Landscape.

A second mystery concerns the study, which appears to be missing about a third of the design on the right side. Indeed, inspection reveals that it was cut down, though when, by whom, and for what reason we do not know. Perhaps the work suffered damage at some point, or perhaps the artist was unsatisfied with some of the passages. And yet the study does not seem to suffer aesthetically as a result of this cut. Davis was operating at the time on his theory of “serial centers”—his idea that a composition should not have a single focus of interest but rather several, much like the multiple masts that punctuate the horizontal frieze of Swing Landscape. This principle gives the painting its even-handed energy, its all-over distribution of forms, which foreshadows in uncanny fashion the paintings of Jackson Pollock, especially such horizontal compositions as his Mural (1943), executed for Peggy Guggenheim’s apartment only six years after Swing Landscape. The success of Study for Swing Lanscape as a painting in its own right testifies both to the validity of Davis’s theory and, perhaps more importantly, to the power of his forms to hold their own, no matter how reduced or truncated.

Technical Summary

The painting is executed on a plain-weave, medium-weight, pre-primed canvas. The priming is a dark gray color. The canvas is lined with a linen fabric of similar weight with a wax adhesive, and the two are tacked with staples and stretched to a five-member, expansion bolt type stretcher that is not original. Wherever the painting has been pulled over the edge of the stretcher bar, both the ground and the paint are extensively broken. There is a good amount of original canvas with intact ground serving as the tacking edges on the top, bottom, and left sides, where it is apparent that the painting is stretched close to its original dimensions. However, on the right side the original tacking margin appears to be missing. There is only a quarter-inch-wide swath of original paint folded over the right edge to serve as a tacking margin. Because there are no tack holes, it does not appear that this originally served as the tacking margin and it seems likely that at one time the painting was wider and has been cut down on this side.

The paint is applied thickly with high impasto and brushwork that is evident in every area. This application follows a precise plan created by a pencil drawing that is visible to the naked eye at the edges of some design elements. For the most part, each design element is painted right up to the adjacent ones, rarely overlapping. This visual characterization is confirmed by the infrared examination. In addition to the pencil drawing, the infrared examination shows the structure of an additional, but later painted over, design element to the right of the ladderlike passage in the upper left. The paint layer appears to be in excellent condition with a fine network of cracks running throughout. However, according to the conservation files of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the painting has been treated several times in the past three decades for extensive areas of flaking paint. In some of these treatments wax was used as a consolidant, and in others Beva-371 was used. Despite the flaking issues there are very few losses visible in ultraviolet light. There are only a few small losses seen in some of the design elements. However, there is extensive retouching along all four edges. There appears to be no varnish or only a light varnishing of synthetic resin applied to the paint layer. In general, the paint appears evenly matte. According to the Corcoran Gallery of Art conservation files, a spray coating of B-67 was applied to the surface in 1978, but then the painting was cleaned, lined, and inpainted in 1979. Presumably this B-67 layer would have been removed in this cleaning. According to the Corcoran files, a spray of B-72 varnish was applied in this second treatment, which is presumably still there because there is no additional treatment record that attests to its removal.