American Paintings, 1900–1945: The White Clown, 1929

Publication History

Published online

Entry

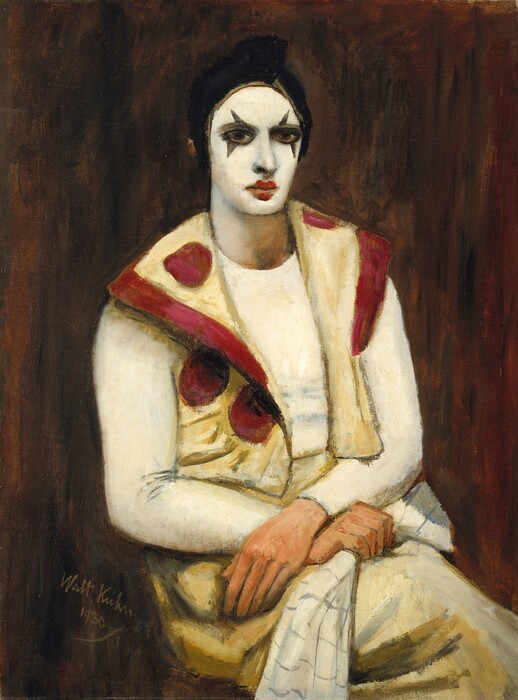

The White Clown was an instant success when it made its debut at the Museum of Modern Art exhibition Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans in December 1929. Arguably Walt Kuhn’s best-known painting and the work that firmly established his reputation at the age of 51, it was reproduced numerous times during his life. Philip Rhys Adams noted that it was “a symbol intensely personal to Kuhn,” and his “passport to immortality.” When the artist’s friends and patrons W. Averell and Marie Harriman immediately offered to buy the painting for $10,000 the artist refused, saying that it was his “ace in the hole” and that it was “not for sale until I’m gone.” When the Harrimans finally purchased The White Clown for $25,000 from his widow in 1957, the event was a national news item. Life magazine noted the sum was “an unparalleled amount of cash for a contemporary American painting,” and allotted it a full-page color illustration.

In his study of Kuhn, Paul Bird described The White Clown as “peak performance in bulk, weight and substance. Like an animal crouched for the kill, he might instantly charge into his routine. Action strains at the bit. With the simplest colors—virtually black and white—the figure is modeled into a throbbing arabesque, fitted exactly to the canvas. Monumentality in a 30" x 40" area.” The clown’s athletic physique fills the large, monochromatic composition. He leans forward and looks directly at the viewer, resting his elbows on his thighs and clasping his large, powerful hands between his knees.

Throughout his career Kuhn was noted for his sympathetic, searching representations of circus, vaudeville, burlesque, and nightclub entertainers. Rather than representing glamourous, spectacular circus acts, as John Steuart Curry did in The Flying Codonas (1932, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), Kuhn instead turned his attention to the rank and file performers, especially clowns. Commenting on Kuhn’s Clown with Black Wig , Bird noted that “clowning is an ancient, legitimate profession with relatively as many master performers, apprentices, and pretenders as any other profession.” In addition to clowning, there was another layer of performance and masquerade at play in The White Clown. Kuhn recorded that the model was in fact an actor named Teddy Bergman (1907–1977), who at that time was engaged at the Provincetown Playhouse and in 1929 also posed for Athlete (Jewett Art Gallery, Wellesley College, MA) and Performer Resting (The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC).

Kuhn drew upon many sources to create The White Clown. His interest in ancient Greek sculpture is reflected in the figure’s angular, geometric, and monumental form. Like the subject of the famous Le Grand Gilles by Watteau , the melancholy expression of Kuhn’s clown invites the spectator to muse over the inherent contradiction between public performance and private angst. The White Clown invites further comparison with the many images of clowns and circus performers by Pablo Picasso, and the painting is reminiscent of the Spanish artist’s classicizing period of the early 1920s. Kuhn met Picasso while attending the Exposition Trinationale at Durand-Ruel Galleries in Paris during the summer of 1925, just four years before he executed this work.

Kuhn continued to return to the clown theme for the rest of his career, perhaps most successfully with The Blue Clown . He identified with his subjects, and his many images of clowns may have autobiographical implications. He specified that Kansas (1932, Ebsworth Collection) be posthumously renamed Portrait of the Artist as a Clown. It has also been suggested that the intense, manic facial expression of Chico in a Top Hat (1948, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York) was a portent of his mental breakdown that year. However, Kuhn would never again paint a psychological portrait so imposing, poignant, and sublimely balanced between physical strength and dignified pathos as The White Clown.

Technical Summary

The plain-weave, loosely woven, highly textured support is unlined. It has been removed from a previous stretcher and remounted. The current stretcher includes wood shims on both the bottom and right sides, but it is not clear whether these were added to enlarge the original stretcher or a later one. The tacking margins are intact, and a selvage edge is present on the left margin. The creamy white ground was toned with a dark brown, transparent imprimatura; an additional layer of more opaque brown imprimatura blocks out the background. The artist first sketched out the composition with diluted paint in dark earth tones and then applied paint with a pastelike consistency in a range of thicknesses. Shadows were indicated in the initial sketch as hard-edged forms that were later softened by the wet-into-wet application of white paint. The broad areas of highlights were thickly painted with vigorous wet-into-wet brushwork to emphasize the volume of the sitter’s body. Facial details were outlined with a small pointed brush and fluid dark paint. The painting is in excellent condition. The surface is coated with a very thin layer of varnish, on top of which a thin layer of grime has accumulated. Old, discolored varnish residues from a past cleaning remain in the low points of the thickly painted white areas.