Technical Notes

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen

Abstract

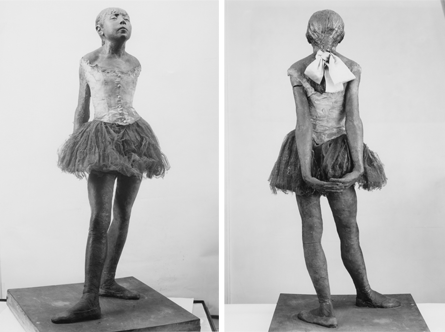

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen is distinguished by its scale, complexity, and range of materials. Furthermore, as the only sculpture exhibited in Degas’s lifetime, Little Dancer raises questions unlike those considered for other works. For example, was her fabrication complex and fastidious because she was always intended for exhibition? Or was it simply because she was so meticulously created that Degas was content to exhibit her? That he originally exhibited an empty case implies the answer is not straightforward. Nonetheless, although the sculpture is different from others by Degas, it is not entirely alien to his corpus.

Publication History

Published online

On this Page:

Fig. 1: Degas, Three Studies of a Dancer in Fourth Position, 1879/1880, charcoal and pastel with stumping, and touches of brush and black wash, on greyish-tan laid paper with blue fibers, laid down on gray wove paper, The Art Institute of Chicago, Bequest of Adele R. Levy, 1962.703. Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago

Study in the Nude of Little Dancer has generally been considered a preliminary attempt at sculpting the youthful dancer in three dimensions even though its relationship to Little Dancer is more complex. Similarly, drawings and sketches for both Little Dancer and Study in the Nude exist (figs. 1, 2).

While there is neither an established relationship between the dates of the drawings nor a precise understanding of their role in the creation of the sculpture, Degas was clearly attempting to render multiple viewpoints in a two-dimensional format. In the charcoal drawing Three Studies of a Nude Dancer (see fig. 2), a small outline in the upper right corner appears to be a sketch for an armature and is particularly relevant to the fabrication of Little Dancer.

Fig 2: Degas, Three Studies of a Nude Dancer, c. 1878, charcoal heightened with white chalk on gray wove paper. Private collection. Photo: Bridgeman Images

Internal Construction

Figs. 1–2

left: Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, radiograph, overall frontal view

right: Schematic diagram of the internal armature of Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. Illustration by Julia Sybalsky and Abigail Mack, 2007

Radiography (fig. 1) reveals that the sculpture is fashioned over a central armature whose construction closely resembles the small sketch noted in figure 2. Identified using XRF as lead, the central armature consists of intersecting hollow pipes approximately 0.5 inch in diameter. It is of interest to note that Degas incorporated somewhat standard armature materials and configuration to make this masterpiece, choosing “lead pipes ½ ″ and 1″ diameter,” an item listed among those Auguste Rodin’s student Malvina Hoffman prescribed as necessary in a sculptor’s studio for fabricating armatures.

One pipe provides a vertical central support that attaches to an inverted U-shaped pipe at the groin, each side of the U extending downward into a leg. Inside the legs, most notably in the right, the pipes were bent to accommodate the pose of the dancer. As observed in the radiograph of the left foot, the pipe was secured by screws into an oblong metal plate on the base. That of the right leg was wrapped using wire to provide texture to the surface so that a clay core could be built up over it. A small sample of the core from the top of the right leg, examined using PLM and SEM, was identified as a water-based air-dried clay (ferruginous aluminosilicate clay), henceforth in this entry referred to as clay.

The complex construction of the figure, emanating from the vertical rod in the body, is repeated at slight variances in the limbs, neck, and head. It can be loosely characterized as often containing an internal organic bulking element bound to an armature, over which clay and ultimately wax are added. In the torso, this internal mass appears to have been roughed out in two stages. The innermost portion consists primarily of pieces of wood held to the central armature with tightly twisted wire. Over this a second layer of organic matter (similar in density to cotton batting) is bound with rope from the groin to just above the waist (fig. 2). A visual aid useful for interpreting the rope-bound core of the torso can be seen in the comparison of the rope core of the fingers and their radiograph (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Detail, radiograph (above) and photograph (below) of Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, showing internal fabrication of the hands

The internal construction also served to rough out the ultimate contour of the dancer’s abdomen. Degas added a layer of padding, anticipating the protruding belly of the adolescent girl over both inner core bundles. Unlike the construction of a period doll, to which the sculpture has been relentlessly compared and whose torso cavity would have consisted merely of stuffing hidden under garments, the fabrication of Little Dancer contains a clay layer over the entire bundle that is then clad in wax. Degas’s use of this technique emphasizes that his process involved modeling a complete figure, primarily working from the inside out and from the feet up except for the arms, which appear to have been attached separately.

Construction of the legs, because they are weight bearing and need to be stable, is slightly different. Clay added directly to the armature pipe from the feet to the knees permanently fixed the position, stabilized the armature, and facilitated modeling. Only at the knees was the inner portion of the clay replaced by a bundle of organic material wrapped with the same gauge wire used around the pipe in the right leg and bound with rope.

Above the section of the torso wrapped in rope, there is a short metal rod perpendicular to the central vertical pipe, of slightly smaller diameter, that extends across the dancer’s chest. Because the rod is inserted between wooden batons through the organic bundle and is incorporated into the wrapping wires, it is likely part of the earliest stage of construction. Degas probably added it to provide support for the separately attached arms. However, in forming them, he deviated from the traditional technique of tying pipes to the central framework to support the appendages. Instead, he added a pair of double strands of loosely twisted iron wire that extend from the right elbow and across the chest but stop abruptly at the left bicep. These wires define a shape or placement but do not provide true support for the arms since they are not tied to the central pipe and may have cracked or broken. When the same area is compared to the photographs for the 1917 – 1918 inventory (figs. 4 –6) and the photographs from the Mellon collection records, possibly sent by Knoedler Gallery to Paul Mellon through the National Gallery of Art at the time of the sale (figs. 7, 8), it is evident that a prominent crack was present in the upper left arm that was subsequently repaired. While it is not possible to corroborate the art historian Paul Lafond’s observation that at the time of Degas’s death Little Dancer’s “arms were broken off from the body and lying pitifully at its feet,” the extant condition of the armature and the surface condition of the wax suggest that portions of the arms could have been broken or even detached from the dancer.

Once satisfied with their positioning, Degas modeled the arms in wax over the wires. Inside, he reinforced the wire armature using a wooden framework, as recommended in sculpture manuals but translated into his own manner by incorporating paintbrushes that run the length of each arm, evident in the radiograph by their slender, tapered handles and metal ferrules, and included in the schematic diagram (see fig. 2). C-shaped wires that secure both arms below the shoulders are evident on the radiograph (see fig. 1). Aware that the dancer’s arms were not adequately supported, Degas may have added the wires, or they may have been introduced posthumously to reinforce areas where cracks existed.

Fig. 9: Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, detail of radiograph, showing head in profile

Moving from the construction of the arms into the head, one sees from the radiograph (fig. 9) that the familiar technique of the wire-wrapped organic bundle, used for the legs and torso, was also employed to form the inner core of the neck and head. On the left side, a wooden baton incorporated within the wires extends beyond the central lead pipe; on the right, a spring of galvanized iron hooked into the wires lengthens the internal support. Surrounding the upper end of the lead pipe, the core bundle continues into the head and neck, providing an inner framework almost entirely at the back of the head. Several layers of clay and wax were then applied to enlarge and define the face and top of the head. A small sample of clay taken from the interior at the nape of the neck, analyzed using SEM-EDS, was identified as the same clay found in the right leg.

Exterior Construction

Degas modeled on the exterior of the sculpture with molten beeswax, which was built up in layers over the clay cladding (see figs. 1, 2). Clusters of long parallel striations, representing successive campaigns of wax application, characterize the dancer’s contours. Varying in thickness from less than 0.5 centimeters at the ankles to approximately 4 centimeters on the shoulders, the wax medium was carefully selected for its malleable properties. Degas’ meticulous manipulation of the medium is beautifully recorded on the surface of this piece. For example, the dancer’s face includes very finely modeled features reinforced using a single-point tool and flesh carefully smoothed using a spatula. A single-point tool reinforced strands of hair in the dancer’s braid, while a spatula and point tool were used together to form the bangs across her forehead. On her arms, repeated diagonal broad-toothed tooling is present, particularly on the upper arm. Even the fourth and fifth digits of both hands, not readily visible, contain carefully rendered finger-nails outlined using a single point tool.

Degas created the illusion of fabric in some areas by tooling the wax. Creases in the dancer’s stockings at the knees are formed using single point tooling. In a similar way, the impression of gathered fabric is created in the wax on top of the feet. On the left shin, a line that resembles a seam extends down the dancer’s tights. Such an illusion is fortuitous, as the seam is created by the interior armature, coated with such a thin layer of wax that the contour of the pipe is recorded.

Microscopic samples taken from the head, hair, bodice, hands, right thigh, and slippers were found to contain beeswax, without added fats, extended with potato starch and pigmented primarily with red and yellow iron oxides, charcoal black, brown earth, calcium carbonate, quartz, lead white, chrome yellows, and chrome oranges. Given the variety of pigments employed, many of which appear in Degas’ palette, it is likely that he toned the wax himself, seeking to simulate flesh tones — in some cases, such as the lips, applying a pink paint directly to the surface, and in other cases mixing pigment directly into the wax matrix. Areas punctuated with unevenly mixed pigment, such as one on the right bicep, further support this explanation of Degas’s process. Writing in April 1881, the critic Charles Ephrussi rued the fact that, “had the work been more finished, the color of the wax would have been better blended, without those dirty blotches that spoil the overall appearance.”

Attire

Bodice

Upon completion of the wax figure, Degas dressed it as the young dancer.[1] For the bodice, he sought a manufactured garment, sewn in cotton[2] faille and tailored to the torso. That the bodice was tailored in situ to suit the dancer’s torso is suggested by the differing widths, loose seams, and skewed placement of the excess fabric gathered on the top edge of the bodice and below the left shoulder. Additional alterations are apparent under the dancer’s arms: on the right the garment protrudes slightly from the armpit, and on the left supplementary wax was employed to compensate for misalignment, possibly due to the manipulation of the shoulder strap.

To slip the bodice over the arms, its shoulder straps were cut. On the right side, the cut edges of the strap were sunk into the wax behind the button; on the left a band of wax used to adhere the two edges is present in front of the button. Once lifted over the head and slipped onto the torso, the bodice was buttoned. From the radiograph, it is evident that the buttons consist of metal casings, identified using XRF as zinc casings,[3] covered in fabric. Unpigmented beeswax, which serves to integrate the garment visually and physically with the sculpture, was applied to the entire bodice.[4]

The bottom third of the bodice appears gray and wrinkled. Possibly when the tutu was removed for posthumous casting of the sculpture, the lower areas of the bodice were disturbed, breaking off the original wax in the process and creasing the fabric. Once a mold was executed, an attempt may have been made to straighten the bottom of the bodice, perhaps by adding hot paraffin wax.[5] This observation and the absence of these creases on the bodice in the inventory photographs (see figs. 1–3), coupled with their presence on both the National Gallery of Art’s plaster version and the serial bronzes, substantiate this hypothesis.

Slippers

Degas used real ballet slippers, just as he had used a real bodice, and altered them to fit his dancer before coating them with wax. The slippers were made of finely woven, undyed linen (fig. 4),[6] suggesting that they were practice or children’s slippers to which Degas made several adjustments, as Lindsay discusses in the entry text below. To color the slippers pink, Degas coated the linen with wax pigmented with red lake, pink lake, chrome orange, chrome yellow, lead white, and charcoal black.[7] He cut an existing ribbon from across the instep and attached long cotton[8] ribbons at the backs of the shoes that were wrapped around the dancer’s ankles and tucked under at the back of her leg. Further proof that the slippers are real is the presence of the drawstrings, casually lying on the top toward the toe of the shoes. Degas even cut the toes and squared them to a shape similar to the unused, pink satin slipper discovered among his studio effects.[9] The fabric inset at the heel of the studio slipper closely matches the woven linen of the dancer’s pair as well.

Tutu

While the bodice appears to have been a manufactured garment, albeit adjusted to fit the sculpture, the multilayered tutu was most likely cut from netting and attached directly around the wax figure. The tutu assemblage consists of five layers of netting[10] or fabric, of varying degrees of coarseness and of slightly differing colors (fig. 5).[11] The most familiar, outermost layer (fig. 5a) is a pale, possibly once white, silk[12] tulle with hexagonal-shaped cells. It is gathered with large stitches of a double-strand, coarse thread and fitted around the dancer’s waist. The bottom edge of this layer is cut by hand into V-shaped triangular points resembling the effect of an edge cut with pinking shears but on a much larger scale.

Progressing from outer to inner, the second layer of tutu (fig. 5b) is an open, plain weave, cotton fabric of a light brown, neutral tone. A number of the square interstices are coated with starch, here used as a stiffener.[13] This layer is exceptionally brittle, perhaps aggravated by the starch. The bottom edge has frayed considerably, and very little remains at the front of the statuette.

Present only at the front, the third layer consists of a “dirty” white, possibly starched, silk[14] maline net, twisted in such a way that the mesh has diamond-shaped cells. It is gathered on a string and hangs in full, rounded pleats from the waist (fig. 5c). Similar to the outermost layer of the tutu, this panel is cut so that the bottom edge is in V-shaped triangular points.

The fourth layer (fig. 5d) is made from a light brown cotton [15] filet net with a square mesh. In addition to serving as a tutu skirt layer, some of this fabric wraps between the figure’s legs.

Layer five, the innermost layer (fig. 5e), is made from an open, plain weave, light brown, cotton fabric [16] similar to that of the second layer, but it is not used for an actual tutu skirt. This fabric hugs the figure’s lower abdomen and is carefully wrapped between the legs, serving as culottes for the dancer.

Careful analysis of the extant tutu layers together with inventory photographs (see figs. 1–3) and the 1955 / 1956 photographs (see figs. 6, 7) reveals some striking comparisons that suggest the tutu is the same as the one pictured in the inventory photograph. As no conclusive documentation has yet been discovered regarding an actual change in the sculpture’s tutu, and given its extremely fragile condition and numerous layers of different netting, the possibility still exists that the extant tutu is indeed the one Degas exhibited in 1881, with possible enhancements added over the years. By the time of Degas’ death, the outer layer of the dancer’s skirt was already short, close to the present length of the entire tutu assemblage, with large sections detached and hanging loose. In the inventory photographs, the bottom edges of both the top layer and the next visible layer appear to have V-shaped triangular points; today the first and third layers have the same kind of bottom edge. The second and fourth layers are much deteriorated and irregular, and by 1955 had been cut to the same length as the outer layer. Furthermore, the creases and wax drips visible on the tulle appear to be the same ones pictured in both the 1918 and 1955 views. According to Paul Mellon’s staff, the tutu was not changed after he purchased the collection.[17] As Lindsay describes in the discussion of historical issues in the entry text below, consideration was given to changing the badly deteriorated tutu but in fact this does not appear to have occurred. That there are five layers alternating between silk and cotton, both net and plain weave fabric, now all desiccated and brittle, speaks to the age of the fabrics and the tremendous amount of care Degas took to provide his dancer with realistic apparel. Neither the bronzes nor the plasters were given such elaborate tutu assemblages.[18]

Hair

Degas used a braided wig of human Caucasian hair[19] to coif his dancer, purchased perhaps from the doll-maker Mme Cusset.[20] Questions as to when the wax on top was applied, particularly given that Degas selected a real wig for her hair, have been raised repeatedly in the literature.[21] Examination of the tresses below the wax reveals that the hair color of the wig is in fact dark blond. Louisine Havemeyer recalled, “How woolly the dark hair appeared,” suggesting that already in 1903 dirt or wax darkened her hair.[22] Clearly Degas applied some wax over the hair as part of the original fabrication. In fact, analyses reveal that this wax is the same as that from the rest of the figure.[23] To attach the braid, it was wrapped in silk[24] ribbon inserted into a hollow at the back of the dancer’s head and held in place by squeezing wax around the bundle of hair at the nape of the neck. This bundle of hair may also have been wrapped in a grosgrain ribbon, an impression of which is visible in the soft wax.[25] As he did with the bodice, Degas used wax to integrate the garment visually and physically with the sculpture, fully manipulating the versatility of his medium. On the one hand, the wax formed part of the adhesive process of the hair. On the other, by tooling the wax to simulate hair on the top of the dancer’s head, the hair became visually blended into the sculpture.

Conclusions

The technical examination of Little Dancer uncovers some of the intricacies of its facture, yet as is often the case, many questions linger. One of the most vexing remains the inspiration for the method of manufacture; it is both traditional and innovative. Degas translated into his own practice the making and modeling of a sculpture from inside out, commencing with a customary metal armature augmented with paintbrushes and springs that he filled with a rope-wrapped organic core bundle, first coated in clay and finally clad in the wax he modeled, tooled, pigmented, and even painted. The fabric, netting, and hair additions came later. Little Dancer is neither a doll, having appendages and head made of wax with mere stuffing for the body, nor an anthropological specimen fashioned with rigorous scientific finesse. Furthermore, such a complex procedure, one he never again duplicated, argues that Degas was not working entirely alone; it is likely that he would have required assistance with technique, or at the very least with procurement of materials. Hence, this work can be added to a growing list of sculpture that required collaboration.[1] Many of the modeling materials employed in the assemblage are the same as those found in other works, yet the final product is unique.[2] Findings addressed herein merely create avenues for further study, some addressed in Lindsay’s entry text below.

Provenance

The artist, Paris; his five heirs; possibly sold separately from the other lifetime works before 1929 or after 1931, to (A. A. Hébrard, Paris);[3] his widow, Mme A. A. Hébrard, and/or his daughter, Nelly Hébrard, Paris; consigned 1955, with most of the other lifetime works, to (M. Knoedler and Company, Inc., New York); sold May 25, 1956, to Paul Mellon, Upperville, Virginia.

Exhibited

6me Exposition de peinture . . . , 35, boulevard des Capucines, Paris, 1881, cat. 12 (exh. cat. Impressionist 1881). Galerie A. A. Hébrard, Paris, 1920 (no exh. cat. known).[4] Exposition des Sculptures de Degas, Mai – Juin, 1921, Galerie A. A. Hébrard, Paris, 1921, cat. 73 (exh. cat. Hébrard 1921, annotated addition under “Divers”). Exposition Degas au profit de la ligue franco-anglo-américaine contre le cancer, Galerie Georges Petit and Galerie A. A. Hébrard, Paris, 1924, possibly cat. 290 or not in exh. cat. (exh. cat. Petit 1924).[5] Possibly Trois siècles d’art français, Paris, 1920s – 1930s (no exh. cat. known).[6] Possibly Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1929.[7] Edgar Degas, 1834 – 1917: Original Wax Sculptures, M. Knoedler and Company, Inc., New York, 1955, cat. 20, as Ballet Dancer, Dressed (exh. cat. Knoedler 1955). Sculpture by Degas, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 1956 (no exh. cat.). Art for the Nation: Gifts in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, 1991 (exh. cat. Luchs 1991, unnumbered). An Enduring Legacy: Masterpieces from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, National Gallery of Art, 1999 – 2000 (no exh. cat.).