Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Lady and Gentleman on Horseback, c. 1655, reworked 1660/1665

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Although the hunt became a popular pastime for Dutch patricians in the second half of the seventeenth century and numerous representations of the sport exist, Cuyp was the only Dutch artist to create large-scale formal portraits of aristocrats engaged in this activity. Lady and Gentleman on Horseback, which is the largest and most imposing of these works, is unique in that it represents an elegant equestrian couple, probably a husband and wife, setting out for the hunt. With an expansive light-filled arcadian landscape stretching behind them, they embark with two types of hounds: tufters to track the deer and follow the scent and greyhounds (under the control of an attendant) to run after the deer and bring them to bay.

The names of the sitters are not known with certainty. Nevertheless, a promising clue to their identity is a bust-length portrait, based on the male rider in this painting, which has been traditionally identified as Adriaen Stevensz Snouck (c. 1634–1671). Alan Chong, who discovered the resemblance between the two heads, has noted that Snouck, originally from Rotterdam, lived in The Hague until his marriage to Erkenraad Berk Matthisdr (1638–1712) in 1654. This marriage would have brought Snouck into contact with Cuyp since Erkenraad was the daughter of Matthijs Berk, Raad-Pennsionaris of Dordrecht and an important patron of the artist. This theory may well account for the prominence given to the female sitter, who, resplendent in her gorgeous blue dress, is mounted on a white horse with a brilliant red and gold saddlecloth.

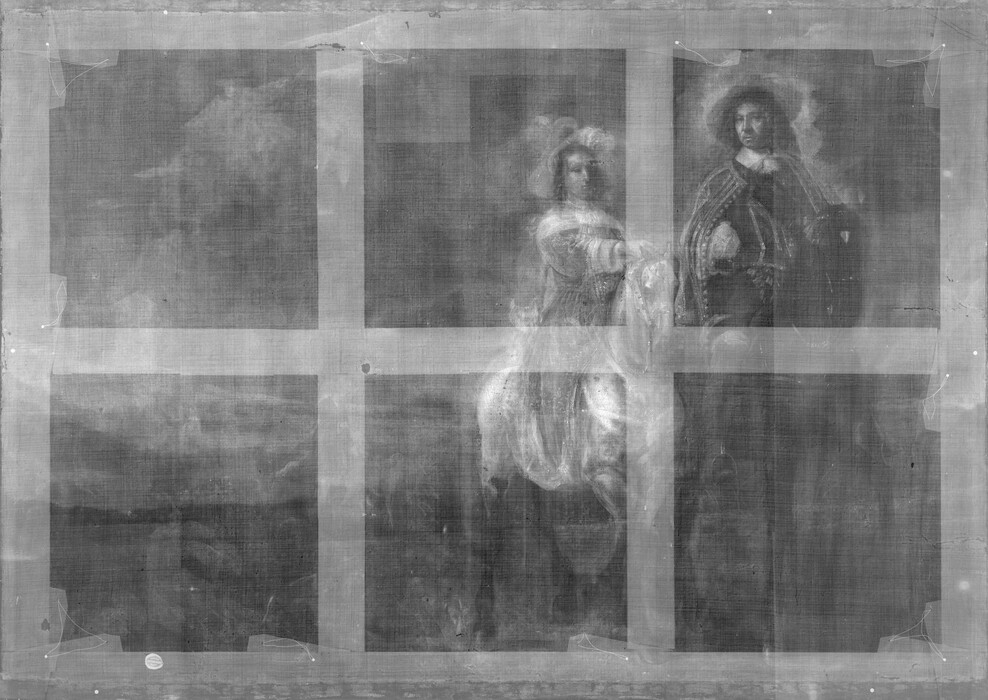

Chong’s identification of the sitters accords well with technical examinations of the painting. As is evident in the X-radiographs [see X-radiography] , Cuyp overpainted and changed major portions of Lady and Gentleman on Horseback. The man originally wore a hat and had shorter hair, and his collar lay flat on his shoulders. He also wore a military-style tunic-and-cape combination, adorned with braids and buttons (presumably gold). This costume, the overall color of which was apparently a brilliant red rather than the current brown, was in many respects similar to that worn by Jan Six in Rembrandt’s famous portrait of 1654, in the Six Collection, Amsterdam.

The woman’s costume was also substantially changed. Her hat was a different shape and its feather sat farther back on her head; her dress fit more loosely and seems to have fallen over the right flank of her horse; and instead of her fairly low, elegantly gathered neckline, Cuyp originally had painted a plain flat collar that covered the woman’s shoulders. The costume was comparable to that seen in Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670)’s 1654 portrait of Abraham del Court and Maria del Keerssegieter . From the stylistic characteristics of the outfits in Lady and Gentleman on Horseback, one can conclude that Cuyp painted the original version in about 1654–1655. As this probable period of execution coincides with the 1654 date of the marriage of Adriaen Snouck and Erkenraad Berk, it is possible that Cuyp received the initial commission to commemorate that event.

Aside from making changes in the figures’ costumes, Cuyp also substantially modified the mood of the painting by altering the woman’s pose and the arrangement of figures in the landscape. The woman originally assumed a less demure position, with her right arm extended, presumably to hold the reins tightly. This gesture would have given her a more active appearance than is evident in the final version. The background was also more dynamic. Instead of the two greyhounds and the young attendant walking behind the riders, Cuyp originally included five running greyhounds and a somewhat larger young man in red socks running with them. The juxtaposition of the portraits and the background figures would thus have been similar to that seen in the painting of the Pompe van Meerdervoort family in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Finally, the landscape also sloped in front from the left, and Cuyp may have made changes to the fanciful castlelike building at the far left.

Although no specific symbolism relating to marriage exists in the painting, the hunt as a theme was metaphorically linked with the game of love. Also, the large burdock leaves in the foreground were frequently associated with love. Cuyp had a special fondness for this plant and included it in the foreground of a number of his paintings. In most of these works the symbolic associations of the burdock leaf seem irrelevant to the meaning of the painting, but in this instance, with the dog calling attention to the plant’s presence, Cuyp may have intended to convey its symbolic associations.

The remarkable revisions in the painting suggest that the patrons were dissatisfied with the original composition. One may speculate that the activity of the hunt distracts from the formal character of the double portrait. The substantial modifications in costume, however, also indicate that the sitters wanted to update their image. For example, the male rider’s dignified brown jacket crossed by a sash and his long, wavy hair worn falling over the shoulders only came into vogue in about 1660. Cuyp’s patrons may also have desired a more refined style of portraiture than the artist had provided in his initial version. Indeed, these portraits are remarkably elegant for Cuyp, who is not noted for his nuanced modeling of the human form. Their style reflects that of Maes, Nicolaes, who after returning to Dordrecht in the mid-1650s initiated a new fashion of portraiture in his native city patterned on the model of Dyck, Anthony van, Sir. Maes’ Dordrecht portraits capture the elegant, aristocratic aspirations of a society that had begun to fashion itself after French styles of dress and decorum, and Cuyp clearly learned from this example.

Technical Summary

The original support, a fairly coarse fabric, has been lined with the vertical tacking margins trimmed. Cusping is visible along all edges. Both the top and bottom tacking margins have been unfolded and incorporated into the picture plane. The painting is generally in good condition, although tears are found near the top edge, left of center, and the right edge, near the lower right corner. The canvas was prepared with a double ground: an orange-red lower layer covered by a gray upper layer.

Paint is applied in thin opaque layers. Numerous artist’s changes are visible as pentimenti and with infrared reflectography at 1.2 to 5 microns [1] and X-radiography. The man had shorter hair and wore a brimmed hat, a decorated tunic, and an embroidered cape tied under his plain collar. The woman, whose proper right arm was raised to hold the reins, wore a large brimmed hat pushed back on her head, a cape, and an ornate dress that fell over the horse’s right side. The white horse’s decorated martingale was slung lower. The boy in the middleground was running, accompanied by five greyhounds. Contour changes were made in the seated rider at the far left and in the lower left landscape.

The lining canvas was in place when the painting was treated privately in 1942, and records indicate at least two generations of inpainting were present. Prior to acquisition, discolored varnish and earlier inpainting were removed, and a surface coating of varnish applied. The painting was treated in 1998–1999, at which time the 1942 varnish and inpainting, which had discolored, were removed. During that treatment it was determined that faded yellow lake glazes probably caused discoloration of the leaves in the lower left and smalt degradation probably caused discoloration of the man’s jacket.[2]

[1] Infrared reflectography was performed using a Kodak 310-21X Focal plane array PtSi camera.

[2] Cross-sections of the painting were analyzed by the NGA Scientific Research department using light microscopy as well as scanning electron microscopy in conjunction with energy-dispersive spectrometry (see report dated June 6, 1998, in NGA Conservation department files).