Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Landscape with Open Gate, c. 1630/1635

Publication History

Published online

Entry

This small work, so evocative of the windswept terrain near the dunes along the Dutch coast, captures the essence of early seventeenth-century landscape painting. With free and fluid strokes, Molijn has created a vigorous and animated scene, where sea breezes, which have molded the craggy form of the dead, vine-covered oak tree and the wood slats of the gate and fence, rustle the leaves of trees surrounding the farm. The painting does not have a composed feeling, but appears as though it were a view along a sandy road that we suddenly happened upon. From the low vantage point, nature rather than man takes precedence. The road, gate, and craggy tree are boldly depicted, while the only figures, a shepherd returning with his sheep just over the rise and a man behind the fence, are small and insignificant.

Landscape with Open Gate is not signed, but the attribution to Pieter Molijn is without doubt. Comparisons with his painting Dune Landscape with Trees and Wagon, signed and dated 1626 (Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig), and with his signed pen drawing of the late 1620s, Road between Trees near a Farm , demonstrate the same approach to landscape. In each instance, this Haarlem artist has dramatically broken with pictorial tradition and situated the viewer below the horizon. Within vistas limited by low viewpoints, the roads that pass through the rolling, windswept landscapes have no beginning and no end. Only the small, insubstantial figures traveling just behind the crests of the rises suggest the world beyond. Stylistically, a particularly interesting comparison can be made between the vigorous rhythms of the pen lines in the drawing and the black chalk underdrawing in Landscape with Open Gate, which is visible with infrared reflectography, .

Molijn was one of the most adventurous landscape artists of his day, one who instilled his scenes with an unprecedented sense of realism. Not only did he limit his range of motifs and color tonalities, he also organized his compositions with powerful diagonal accents that were reinforced through strong effects of light and dark. Through these means he gave his paintings both a specific visual focus and a unifying path into the distance. By 1626 his bold and vigorous brushwork had already attracted the attention of Hals, Frans, who asked Molijn to paint the landscape in the celebrated portrait Isaac Abrahamsz Massa (Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto). As early as 1628 Samuel Ampzing praised Molijn for these same qualities in his chronicle of Haarlem. At about the same time, Molijn’s influence in both style and subject matter is evident in the work of his Haarlem contemporary Ruysdael, Salomon van and in paintings by the Leiden artist Goyen, Jan van.

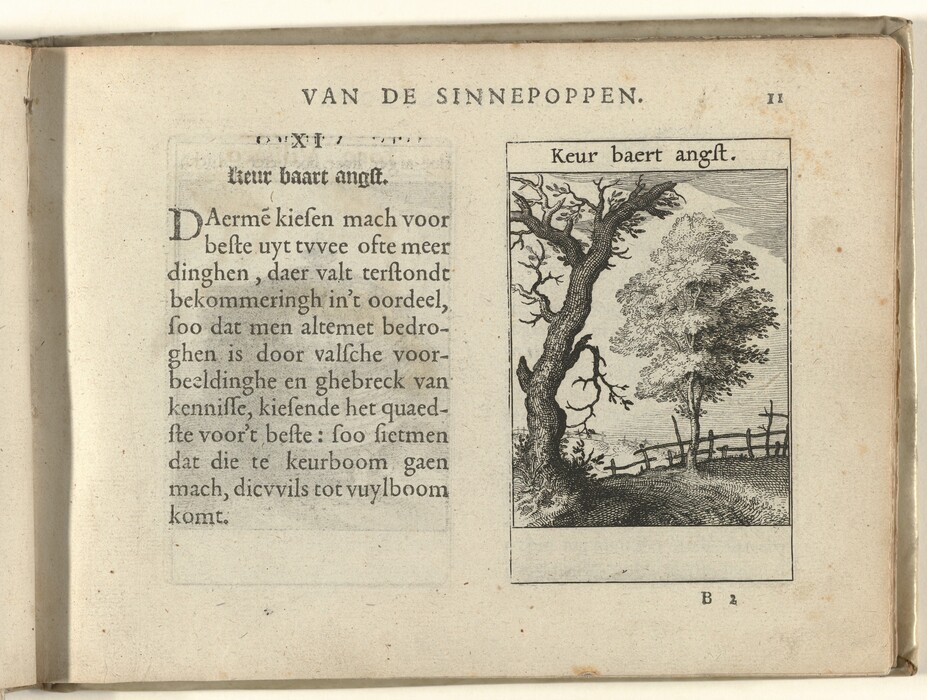

Molijn’s distinctive style of landscape painting owed much to the drawings and etchings of three artists who already had been active in Haarlem at the time he joined the Saint Luke’s Guild in 1616: Velde, Esaias van de, I, Buytewech, Willem, and Velde, Jan van de, II. The restive character of Molijn’s line, however, indicates that he also drew inspiration from other artists, including Gheyn II, Jacques de and Bloemaert, Abraham, whose landscape drawings often focused on old barns and rugged trees. While Molijn’s historical importance lies in his ability to translate these precedents into painted images, ones that helped usher in the tonal phase of Dutch landscape painting, he may have translated thematic concepts as well. Dilapidated farms and starkly silhouetted dead trees would have been understood in moralizing terms by some of his contemporaries. The dead tree in Landscape with Open Gate may have called to mind Roemer Visscher’s emblem “Keur baert angst” (“Choosing causes anxiety”) , which juxtaposes a rotten and a healthy tree to stress that false appearances and lack of knowledge often lead one to make wrong choices in life. This tree could also have been seen as a reminder of the transience of life, an idea taken up with even greater force somewhat later in Haarlem by Ruisdael, Jacob van (see Forest Scene).

Technical Summary

The support, a single, horizontally grained oak board, has several minor cracks parallel to the grain. Dendrochronology has determined a felling date between 1628 and 1634, with the most plausible date being 1630.[1] The back is wax-coated and the edges beveled. The double ground consists of a lower white layer and an upper light brown layer. The smooth, thin ground masks the wood grain and is extensively incorporated into the design. The fluid, brush-applied strokes of the extensive underdrawing, which is more agitated and oblique than the final composition, are readily visible to the naked eye as well as with infrared reflectography at 1.5 – 1.8 microns.[2] The two small foreground figures, which do not appear in the underdrawing, seem to be later additions.

Translucent paint is applied thinly and rapidly, with slightly impasted highlights and stiff brushwork in the sky. Frequently the ground is merely glazed over lightly or highlights applied to exposed underdrawing lines, as in a quickly executed sketch. Discolored inpainting covers scattered small losses and reinforces lines in the gate and the figures to its right. Remnants of aged varnishes indicate selective cleaning in the past. The painting has not been treated since its acquisition.

[1] Dendrochronology was performed by Dr. Peter Klein, Universität Hamburg (see report dated January 7, 1987, in NGA curatorial files).

[2] Infrared reflectography was performed using a Santa Barbara Focal plane array InSb camera fitted with an H astronomy filter.