Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century: Portrait of the Artist's Parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna Westerbaen, 1664

Publication History

Published online

Entry

Jan de Bray painted this remarkable double portrait of his parents in 1664, shortly after they had succumbed to the plague that ravaged Haarlem from 1663 to 1664. The stark double-profile pose gives this image a timeless quality that is enhanced by the sitters’ simple black dress and the dark, greenish-black cloth hanging behind them. Jan represented his father, Salomon (1597–1664), with his left hand outstretched as though he were about to speak, a rhetorical pose that identifies him as a man who excelled at intellectual pursuits. Such associations are reinforced by the black skullcap, dark mantle, and simple white collar—all common elements of scholarly attire. Anna (c. 1605–1663), the painter’s mother, is depicted in similarly sober fashion, wearing a pointed skullcap and a fanciful silk cloak.

Salomon de Bray was a painter, architect, and urban planner who probably learned to paint in his native Amsterdam before moving to Haarlem to study with Goltzius, Hendrick and Cornelisz van Haarlem, Cornelis. Following their teachings, which emphasized a theoretical foundation, Salomon soon took on a leading role in Haarlem as a classicist artist. In the 1630s he was a key player in the reorganization of the Saint Luke’s Guild, a reform that rewarded leading painters and architects with positions of authority in the guild. As an architect and urban planner, Salomon sought to bring classical order to buildings as well as to a planned (but never realized) expansion of Haarlem. A devout Catholic, he was also a poet and a member of the rhetorician’s society. Anna Westerbaen, who married Salomon de Bray in 1625, came from an intellectual and artistic family in The Hague. She was the sister of the poet and physician Jacob Westerbaen (c. 1600–1670) and of the portrait painter Jan Westerbaen (c. 1600–after 1677), who may well have instructed Jan de Bray in the art of that genre.

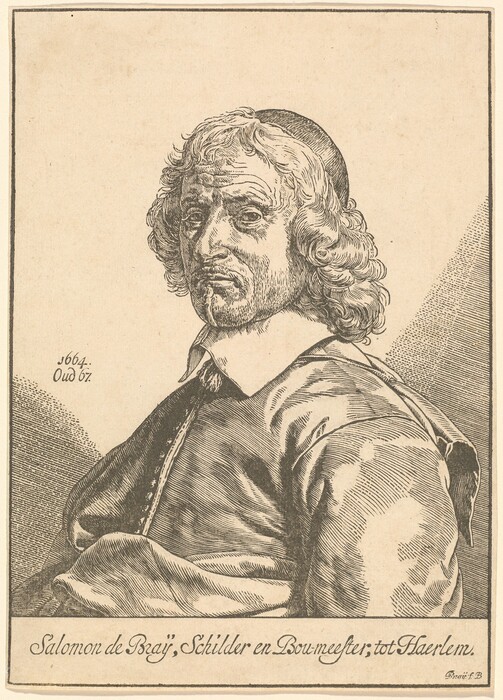

De Bray presumably painted this work between May 11, 1664, the date of his father’s death, and June 17, 1664, when the artist stated in his will that he would bequeath “the likeness of his foresaid deceased father and mother standing in a single piece and painted from the side” to Gaeff Meynertsz Fabritius (1602–1666), who was a goldsmith and, like Salomon, an important member of the Saint Luke’s Guild. It is more significant, however, that in 1664 Fabritius served as burgomaster of Haarlem. De Bray stipulated that Fabritius would receive this double portrait, as well as a (now-lost) self-portrait, on the condition that the burgomaster would in turn bequeath the two paintings to the city of Haarlem. This requirement indicates that De Bray saw these works as commemorative portraits to be viewed and admired by future generations of Haarlem's citizens. De Bray outlived Fabritius, however, hence the terms of this bequest were never realized. The painting’s subsequent history is unknown until 1868, when it was sold in Paris as part of the J. C. Robinson collection (see Provenance). In 1664 Jan, in collaboration with his brother Bray, Dirck de, who was a printmaker, produced a second commemorative portrait of his father , a woodcut image based on a drawing he had made in 1657 (Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin).

Technical examinations indicate that De Bray initially painted Salomon’s left arm hanging at his side: x-radiographs [see X-radiography] reveal a series of vertically angled highlights that accented the inner edge of his upper arm when it was in that position . In the first stage of the painting Anna wore a dress with a pleated white collar. The important compositional change in the position of Salomon’s left arm may have required a modification in the painting’s format. De Bray extended the original panel with additions at both the left and the right, presumably to provide more space around the figures.

The profile portrait was a common format on Roman coins, cameos, and celebratory medals depicting individuals of high birth and rank. This tradition was revived in Renaissance portraits of famous men and women and is also found in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, specifically in representations of the Prince and Princess of Orange painted in the early 1630s by Honthorst, Gerrit van and Rembrandt van Rijn. Salomon, too, had used the format in a painting of a young woman in strict profile from the 1630s. Jan de Bray’s use of overlapping profile portraits, however, is rarely found in seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting. Among the few precedents is Agrippina and Germanicus, c. 1614 , by Rubens, Peter Paul, Sir. Rubens, who studied and collected antique cameos and medallions, explicitly adapted this format for this painting of Roman aristocrats. Even more pertinent to the conceptual ideas underlying De Bray’s painting is a double portrait of the artist and his wife by the Antwerp master Hendrik van Balen (c. 1574/1575–1632), meant to be placed above their tombstone. The profile format was used often for portraits of the deceased. Whether or not De Bray was familiar with these Flemish evocations of a cameo double portrait, he chose a similar pose to imbue his parents’ image with classical ideals of dignity and permanence.

De Bray’s restrained brushwork and meticulous modeling of forms perfectly complemented the commemorative nature of this double portrait. He precisely rendered the specific physiognomy of each of his parents, from his mother’s high forehead and curved nostrils to the subtle creases around his father’s deeply set eyes. With great sensitivity to both line and volume he indicated the glistening strands of Salomon’s wavy hair and thin goatee. He captured the differences of texture in the clothes, from the soft, velvety quality of his father’s black robe to the smoothness of his stiff white collar, carefully bending up its lower edge to enhance the image’s three-dimensionality. Unlike his Haarlem compatriot Hals, Frans, whose broadly brushed and freely rendered portraits suggest both physical and psychological movement, De Bray achieved the lifelike character of these posthumous portraits through the sitters’ penetrating gazes and the sheen of their skin, and through Salomon’s restrained yet rhetorically eloquent gesture. Through these means De Bray sought to keep the dead alive in the memory of the living.

Technical Summary

The painting was executed on a panel constructed from three boards of vertically grained white oak.[1] The back of the panel is beveled but shims have been attached to the beveled areas to accommodate a cradle. The ground is composed of two layers: a light gray layer under a brownish gray one. Though the green background paint was found to be consistent on all three boards, the layers between the ground and the green paint differ. Both the right and left boards contain a dark gray layer over the ground. This layer is absent from the center plank, but both the center and left boards contain a buff colored layer just below the green background, which is absent from the right plank. Despite these inconsistencies, the pigments of the green paint are consistent on all three boards[2] and the brushstrokes of the green paint continue across the joins, indicating that the two outer boards were added by the artist before the background was painted.

De Bray used a series of short, discrete brushstrokes to apply the paint with low impasto. He built up the flesh tones with opaque paint, but used glazes in the dark areas. The X-radiographs show several artist’s changes: the woman’s dress was simplified and it originally had a collar that was painted out; the man’s arm was not originally raised.

The painting is in good condition. The panel exhibits a few short vertical splits extending down from the top edge and up from the bottom edge. There are minor scattered indentations and chips in the support along the edges. There is old damage in the lower right corner adjacent to the join line. The inpainting in this area has discolored. There is additional old inpainting in the man’s sleeve, close to his wrist. The painting has not undergone treatment at the National Gallery of Art.

[1] The wood was analyzed by the NGA Scientific Research department (see report dated December 29, 2010, in NGA Conservation department files). All three boards were found to be white oak.

[2] Cross-sections from all three boards were taken and analyzed with light microscopy as well as scanning electron microscopy in conjunction with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) by the NGA Scientific Research department (see report dated December 29, 2010, in NGA Conservation department files).