Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.

With music playing and a barrel full of wine, this 16th-century Italian painting seems at first to be about pleasure. But it also tells fascinating stories about power. We see not only the divinely powerful gods but also three painters, each trying to assert their vision on this canvas.

The Feast of the Gods depicts a scene from Ovid’s Fasti. Dating to 8 BCE, these tales of Roman gods inform how we celebrate special occasions today. In the story shown here, Priapus, the lustful god of fertility, tries to lift the gown of a nymph named Lotis while at a party. Lotis is asleep, unaware of his advances. According to the legend, the donkey at left is about to bray, waking Lotis and scaring off Priapus.

As the painting’s suggestive—and disturbing—subject matter might indicate, it was not meant for public viewing.

The Wealth of Duke Alfonso’s Court

Alfonso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, asked Venetian artist Giovanni Bellini to create this painting in the early 1500s. It was to be the first in a series of works for the grand camerino d’alabastro (alabaster study) of the duke’s castle in Ferrara.

Alfonso d’Este was a great patron of the arts. He planned to decorate the walls of his camerino with several large, expensive paintings by renowned artists such as Bellini.

The opulent camerino was the duke’s private office, and only a select few were allowed in. So this hedonistic scene was meant only for him—and perhaps his close friends and advisors.

The work is full of references to the wealth and influence of Duke Alfonso’s court.

Such coveted items would have traveled to Europe via the Silk Road, a network of trade routes from Asia. Including them in this painting points to Italy—and specifically Ferrara—as an influential presence in global trading networks.

Party of the Gods

While The Feast of the Gods was meant to demonstrate Duke Alfonso’s earthly, material power, it is also brimming with divine power.

The painting is a veritable who’s who of Roman gods and goddesses. Clues throughout the work help us identify them.

The Work of Three Painters

Giovanni Bellini created this work during the Italian Renaissance, when individual artists were gaining influence and recognition.

While Bellini was the first to work on The Feast of the Gods, two other great Renaissance artists contributed as well: Dosso Dossi and Tiziano Vecellio (also known as Titian).

After Bellini’s death in 1516, Dossi and Titian made significant changes, including adding the large, rocky landscape to the background. Thanks to conservation work done on the painting, we can see what it probably looked like before their alterations.

Dossi, known for his delicately feathered trees, may have added the ones in the upper right corner. They look like the beautiful foliage in his other works, such as The Trojans Building the Temple to Venus and Making Offerings at Anchises’s Grave in Sicily (painted around 1520).

He also likely added the pheasant that appears in the trees’ upper branches.

Titian, The Bacchanal of the Andrians, 1523–24, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520-3, oil on canvas, National Gallery London

Titian made other paintings for Alfonso’s camerino, including Bacchanal of the Andrians and Bacchus and Ariadne (both painted in the early 1520s). His changes to The Feast of the Gods may have been meant to harmonize it with the rest of the duke’s collection.

In this work, we see the mastery of three great Italian artists. Ultimately, it is their skill—more than Duke Alfonso’s power or the majesty of the gods—that makes this painting so memorable.

You may also like

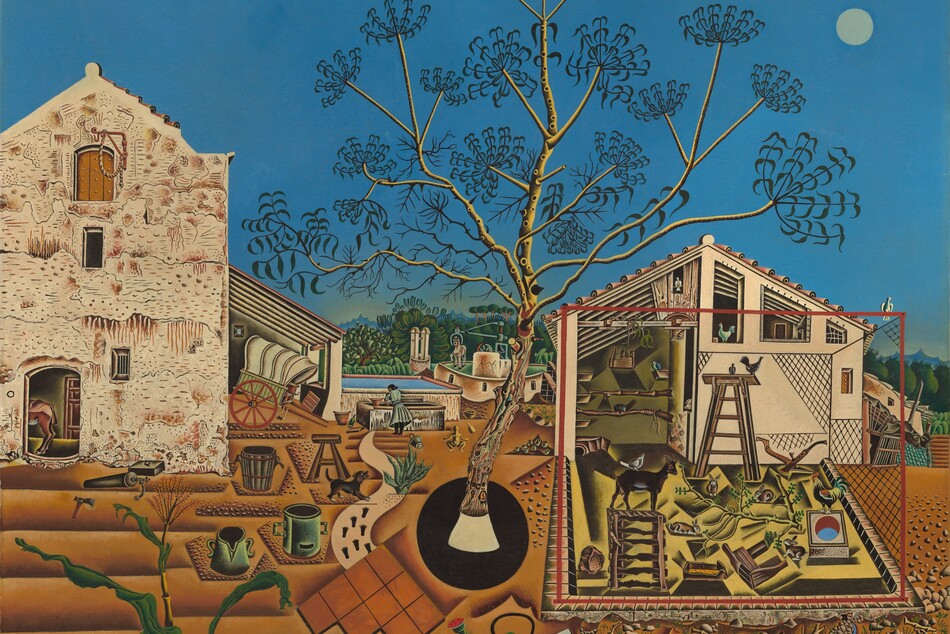

Interactive Article: Art Comes to Life in Joan Miró’s "The Farm"

Joan Miró’s complex and captivating painting is full of life and mystery.

Interactive Article: Art up Close: Judith Leyster, the Leading Star of Her Time

Her paintings were passed off as the works of her male contemporaries. Get to know 17th century painter Judith Leyster through the hidden details of her lively self-portrait.