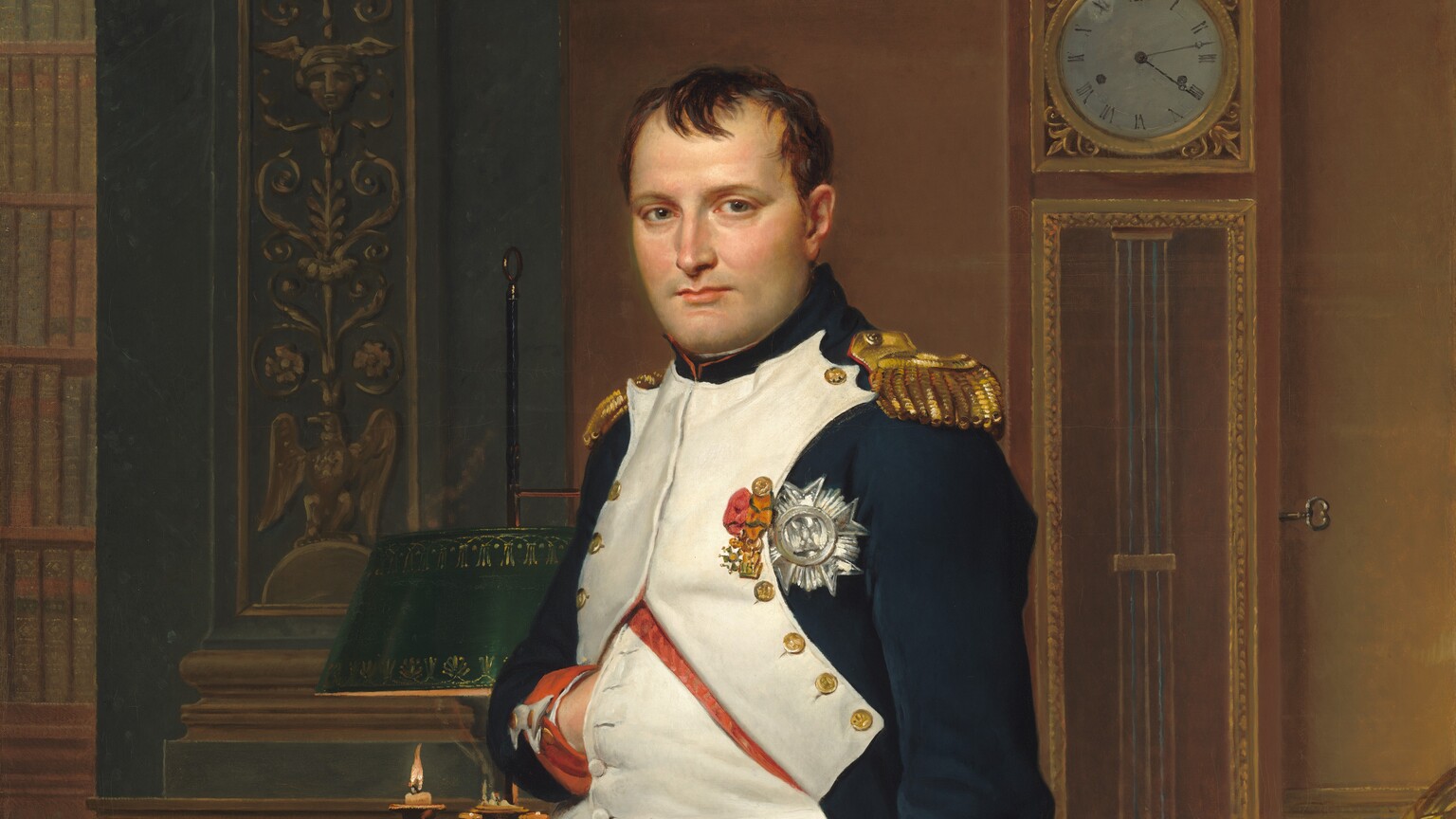

Art up Close: Jacques-Louis David’s Mythical Napoleon

A look at the details in this imagined portrait of the legendary French emperor.

Jacques-Louis David was the leading portraitist of his day in France. He was known for his ability to capture the likeness of his sitters. But he was even more skilled at communicating the personalities and accomplishments of his subjects.

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study in the Tuileries is one of the ultimate examples. David filled the portrait with precise details, portraying Napoleon as a living legend.

Take a scroll with us through the painting and see how Napoleon’s appearance, the setting, and the items create a myth of an ideal leader. See if you can spot David’s signature hidden in the painting.

Napoleon, the Man of the People

The full-length portrait shows Napoleon standing in his study at the Tuileries Palace, his official Parisian residence.

This suggests that Napoleon has been working late on the Napoleonic Code, France’s first code of civil laws. It created a unified set of laws for the entire country. David shows Napoleon as a dedicated legislator, working all night on behalf of the people. But the achievement he is working on dates to a decade earlier.

The code was written between 1801 and 1803, and entered into force in 1804, before Napoleon crowned himself emperor later that year. And while the code did abolish privileges based on birth and the feudal system, it did not serve all the people. Women actually lost rights—the laws established them as lesser than their fathers and husbands.

David’s choice to paint the ruler at work was unconventional to begin with. Most royal portraits show kings just being. Dressed in their finest and set in splendor, they embody the state. In earlier portraits of Napoleon, David had followed that tradition.

Hyacinthe Riguad, Louis XIV (1638-1715), roi de France, 1701, Louvre Museum

Jacques-Louis David, Emperor Napoleon I, oil on panel Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Napoleon, the Military Leader

No portrait of Napoleon could be complete without a reference to his military background. David had first won the emperor’s favor with a dramatic portrait of him astride a rearing horse, Napoleon Crossing the Alps.

In reality, “tempered” was not a word many would have used to describe Napoleon. He was known for outbursts. And his desire for power and influence seemed to drive his quest to conquer Europe and create a French empire. His risky and unnecessary military campaigns led many French soldiers to their deaths.

The same year this painting was completed, Napoleon directed an invasion of Russia that would be a massive failure. Five months of battle killed Approximately 1 million French and Russian soldiers and civilians.

Napoleon, the Trendsetter

After completing this portrait, David wrote in a letter, “I have made sure that everything in the picture, down to the smallest detail of costume, furniture, sword, etc., was scrupulously modelled on [Napoleon’s] own.”

While it may be true that all of these were real items, not all would have been found in Napoleon’s study. But David included them to help establish Napoleon as the creator of a new style.

Fine decorative arts were important to Napoleon. He believed they could serve to promote the glory of France. He encouraged a neoclassical style with references to ancient Greek and Roman motifs. It also incorporated Egyptian designs inspired by his campaign in the Ottoman territory. Today, this is known as Empire style.

Napoleon didn’t just encourage borrowing styles from ancient art. He also pillaged and stole works from around the globe. His troops often brought souvenirs back to France from military campaigns. These irreplaceable cultural artifacts filled the Louvre Museum in Paris, renamed the Musée Napoléon during his reign. After Napoleon was removed from power, many works were returned. But several remain on view today, including the iconic Vénus de Milo sculpture and Paolo Veronese’s The Wedding Feast at Cana.

But a throne wouldn’t be used at a desk. Its placement here is symbolic.

How do portraits influence the way we see historic figures? David uses realism and careful details to create a powerful myth of Napoleon as a military leader and lawgiver. But it’s not the full story. In spite of David’s convincing painting, we must reckon with Napoleon’s complicated legacy.

You may also like

Interactive Article: Art up Close: John Beale Bordley’s Revolutionary Portrait

The origins of the Revolutionary War can be found in the details of Charles Willson Peale’s early American portrait.

Interactive Article: Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.